Craig Baute has figured out how to turn a big profit on a small City Park studio.

The 29-year-old owner of Creative Density Coworking purchased the 425-square-foot space in October with his father to rent through Airbnb. The apartment brings in $1,900 each month, and Baute said he pockets about $900 after paying mortgage and utilities.

“After the down payment, we spent about $5,000 to furnish the place and give it a fresh paint job, which is below what we were expecting to pay,” he said.

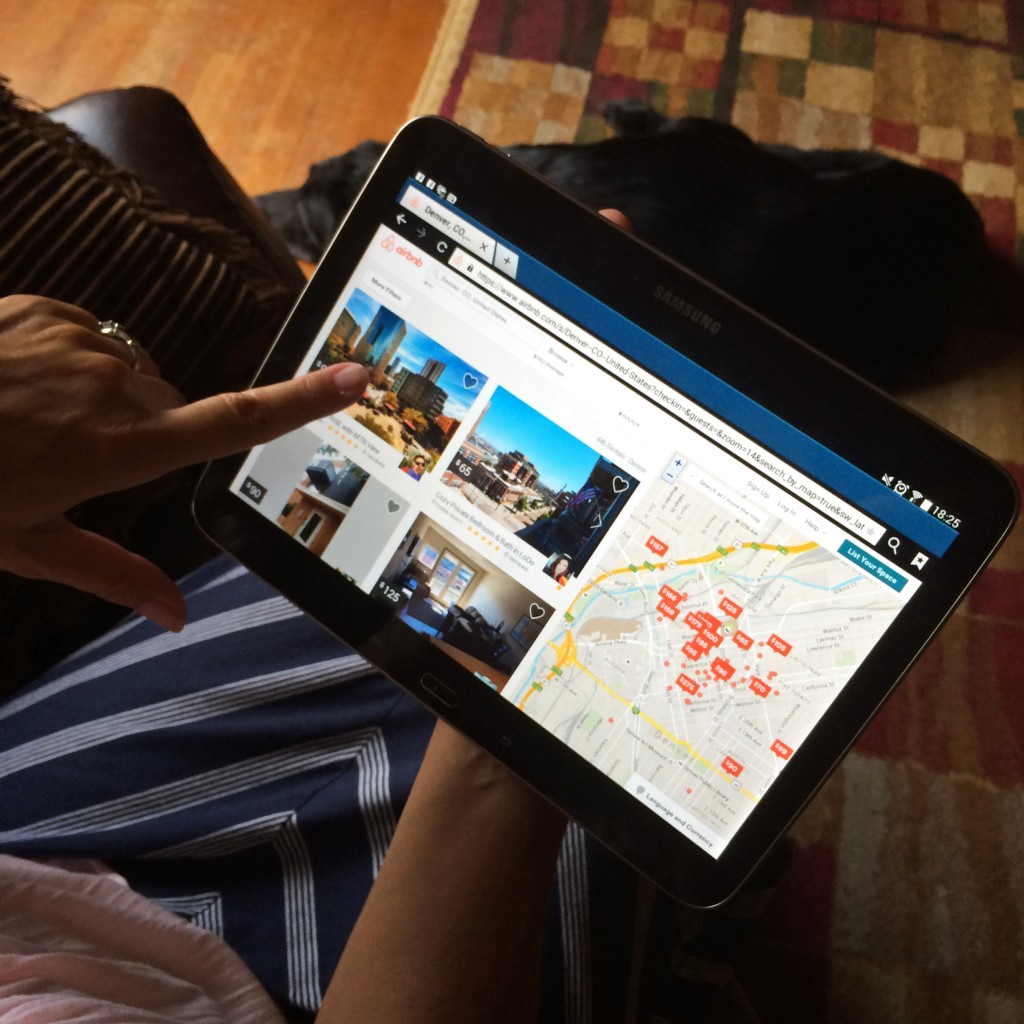

Baute is one of more than 1,000 Denver residents who earn extra cash by listing their apartments, homes and condos on Airbnb, a 7-year-old home-sharing site that enables travelers to skip the hotel and stay in the heart of some of the city’s most sought-after neighborhoods.

It’s an unregulated practice that has left property management companies and city officials scrambling to address issues associated with short-term rentals. Cat-and-mouse games between landlord and tenant play out as the Denver City Council tries to draft regulations that appease both sides – a balance several other cities have failed to achieve.

“As we’ve seen with San Francisco and Portland, regulations can be well-intentioned but hard to enforce and onerous to the hosts,” said Luke Palmisano, an aide to Councilwoman Mary Beth Susman who researches the short-term housing market. “We want to sit down with as many stakeholders as we can to get their perspectives.”

Those who open their doors to Airbnb’s 40 million users often do so in secret; it’s illegal for homeowners to rent out a residence for fewer than 30 days in most areas of Denver, and many landlords prohibit subleasing, citing security.

“Our concern is you have people coming from all over the world with no form of background check,” said Charlie Hogan, COO at Cornerstone Apartment Services, a company with 2,800 units throughout the city.

Airbnb isn’t the only home-sharing site that rents Denver-area properties, but it’s the most popular – VRBO, owned by HomeAway, lists only 373 properties in the city.

Nightly rentals and long-term gigs

The Line 28 building on Boulder Street in LoHi has a one-bedroom unit listed on Airbnb for $157 per night, or $3,500 per month. Photo by Katherine Blunt.

Not everyone who uses the site is breaking the rules. Those who own their residences and rent them out for longer than a month are in the clear if their HOA permits it. Baute typically rents his studio out for three months at a time, a duration he settled on after experimenting with shorter-term rentals.

“We could have done short-term stays at $100 a night and made $2,500 a month,” Baute said. “But that was more work, it was against the HOA, and really our profits weren’t that much higher because we had to pay a cleaner so much more often.”

But in many cases, the lure of profit is stronger than the threat of repercussions for renting a home for just a few days. Hundreds of Denver-area apartments and homes listed on Airbnb require only a one-night minimum stay, generally priced between $50 and $300 a night. For $150 or less, users can rent a room downtown or an apartment in neighborhoods such as Cap Hill and the Highlands. For more than that, the options include LoDo lofts and penthouses and entire homes near the city’s parks.

Cornerstone’s Hogan attributes the site’s popularity partly to the steady rise in the city’s cost of living. Average monthly rent in the Denver area topped $1,200 during the first quarter of the year, according to a survey by the Apartment Association of Metro Denver. It was less than $1,000 in 2012.

On average, people who rent through Cornerstone make $40,000 a year and spend as much as 40 percent of their salary on rent, Hogan said.

“Cornerstone’s demographic is a solid sample of the central Denver market,” he said. “With increased rent rates, this is a way to subsidize your rent.”

Tony Reynolds, a software developer who lives in the Baker neighborhood, rents out two of his properties – one through a traditional lease, one through Airbnb. He began listing his 500-square-foot condo in Breckenridge on the site last month for about $120 each night.

“We booked July and August solid, and that will cover at least four months of mortgage and HOA costs, which are expensive up there,” he said. “What we get in December alone will probably cover three months.”

The apartment that Reynolds rents traditionally is in Cap Hill, and he said his foray into Airbnb has made him wonder whether his tenant there uses the site, too.

“For all I know, he could be Airbnb-ing every time he goes out of town,” he said. “If he asked, I would probably say he could.”

Landlords on patrol

Other landlords aren’t as open to tenants running their own rental businesses. And some crack down on those who try. Venetia Makshanoff, property operations manager at Mosaic Property Management, said the company has started monitoring Airbnb to see if any apartments within its seven buildings are up for rent.

“We have a gated community, so to speak, and these people are renting to someone that they don’t know and we don’t know and exposing other residents to possible harm,” she said. “We’ve worked hard to put into place what we feel is a fair but stringent screening policy, and people are circumventing that by allowing other people to move in.”

Makshanoff said Mosaic first became aware that some of its tenants were subletting their apartments through the site last summer.

“We did some research and found out that we had three people in Capitol Heights and one in Highland Park using Airbnb, and that’s an absolute violation of our lease,” she said. “We gave them notices to quit (their leases).”

One of the tenants hadn’t yet made her first rental, so Mosaic allowed her to stay, Makshanoff said. But the company issued notices to all of its tenants emphasizing that it prohibited Airbnb rentals.

Cornerstone has taken a similar approach. Hogan said members of his staff check the site about once a month for listings in any of the company’s 107 buildings. If one is discovered, the company notifies the tenant and asks that they resolve the issue within three days – something it has done three times within the past two years.

“If the places are owned, I’m pro-Airbnb,” Hogan said. “I have no qualms with that. But when you’re making money off of someone else’s investment, I have a moral issue with that.”

The city weighs in

Last year, the City Council formed a task force to devise regulations that would allow residents to list their places on Airbnb and other sites if they meet certain criteria. A draft of the proposed regulations calls for zoning code revisions to legalize the practice if the home’s primary resident obtains a business license, affirms that the rental has safety features such as smoke detectors and gets permission from an HOA or landlord if necessary.

The task force, led by Councilwoman Susman, will present the draft at a Neighborhoods and Planning Committee meeting Sept. 2, but it will be months before any regulations are finalized. Palmisano, Susman’s aide, said the council might reach a decision by the end of the year.

The council is also considering imposing the city’s 10.75 percent lodging tax on short-term rentals, an idea backed by the Colorado Hotel and Lodging Association. It’s difficult to quantify Airbnb’s impact on Denver’s hotel industry, but Amie Mayhew, the association’s president, said illicit, tax-free rentals have likely had some effect on revenue.

“We are supportive of regulation and, more importantly, taxing short-term rentals,” Mayhew said. “We’d really like it to be a level playing field.”

Airbnb’s growing popularity doesn’t affect all hotels equally. Researchers at Boston University recently examined Airbnb’s impact on Austin’s hotel industry and found that the city’s mid- and low-priced hotels have lost the most business to the site because some travelers see more value in home sharing at those price points.

Many Denver properties listed on Airbnb for similar prices as midrange hotels are in neighborhoods surrounding the city’s core, such as City Park, where Baute’s studio is located. He said he thinks his renters like to experience parts of the city like a local.

“It gets them into the neighborhoods,” he said. “(My guests) usually ask for the best local restaurants within walking distance. That neighborhood experience is very nice.”

Craig Baute has figured out how to turn a big profit on a small City Park studio.

The 29-year-old owner of Creative Density Coworking purchased the 425-square-foot space in October with his father to rent through Airbnb. The apartment brings in $1,900 each month, and Baute said he pockets about $900 after paying mortgage and utilities.

“After the down payment, we spent about $5,000 to furnish the place and give it a fresh paint job, which is below what we were expecting to pay,” he said.

Baute is one of more than 1,000 Denver residents who earn extra cash by listing their apartments, homes and condos on Airbnb, a 7-year-old home-sharing site that enables travelers to skip the hotel and stay in the heart of some of the city’s most sought-after neighborhoods.

It’s an unregulated practice that has left property management companies and city officials scrambling to address issues associated with short-term rentals. Cat-and-mouse games between landlord and tenant play out as the Denver City Council tries to draft regulations that appease both sides – a balance several other cities have failed to achieve.

“As we’ve seen with San Francisco and Portland, regulations can be well-intentioned but hard to enforce and onerous to the hosts,” said Luke Palmisano, an aide to Councilwoman Mary Beth Susman who researches the short-term housing market. “We want to sit down with as many stakeholders as we can to get their perspectives.”

Those who open their doors to Airbnb’s 40 million users often do so in secret; it’s illegal for homeowners to rent out a residence for fewer than 30 days in most areas of Denver, and many landlords prohibit subleasing, citing security.

“Our concern is you have people coming from all over the world with no form of background check,” said Charlie Hogan, COO at Cornerstone Apartment Services, a company with 2,800 units throughout the city.

Airbnb isn’t the only home-sharing site that rents Denver-area properties, but it’s the most popular – VRBO, owned by HomeAway, lists only 373 properties in the city.

Nightly rentals and long-term gigs

The Line 28 building on Boulder Street in LoHi has a one-bedroom unit listed on Airbnb for $157 per night, or $3,500 per month. Photo by Katherine Blunt.

Not everyone who uses the site is breaking the rules. Those who own their residences and rent them out for longer than a month are in the clear if their HOA permits it. Baute typically rents his studio out for three months at a time, a duration he settled on after experimenting with shorter-term rentals.

“We could have done short-term stays at $100 a night and made $2,500 a month,” Baute said. “But that was more work, it was against the HOA, and really our profits weren’t that much higher because we had to pay a cleaner so much more often.”

But in many cases, the lure of profit is stronger than the threat of repercussions for renting a home for just a few days. Hundreds of Denver-area apartments and homes listed on Airbnb require only a one-night minimum stay, generally priced between $50 and $300 a night. For $150 or less, users can rent a room downtown or an apartment in neighborhoods such as Cap Hill and the Highlands. For more than that, the options include LoDo lofts and penthouses and entire homes near the city’s parks.

Cornerstone’s Hogan attributes the site’s popularity partly to the steady rise in the city’s cost of living. Average monthly rent in the Denver area topped $1,200 during the first quarter of the year, according to a survey by the Apartment Association of Metro Denver. It was less than $1,000 in 2012.

On average, people who rent through Cornerstone make $40,000 a year and spend as much as 40 percent of their salary on rent, Hogan said.

“Cornerstone’s demographic is a solid sample of the central Denver market,” he said. “With increased rent rates, this is a way to subsidize your rent.”

Tony Reynolds, a software developer who lives in the Baker neighborhood, rents out two of his properties – one through a traditional lease, one through Airbnb. He began listing his 500-square-foot condo in Breckenridge on the site last month for about $120 each night.

“We booked July and August solid, and that will cover at least four months of mortgage and HOA costs, which are expensive up there,” he said. “What we get in December alone will probably cover three months.”

The apartment that Reynolds rents traditionally is in Cap Hill, and he said his foray into Airbnb has made him wonder whether his tenant there uses the site, too.

“For all I know, he could be Airbnb-ing every time he goes out of town,” he said. “If he asked, I would probably say he could.”

Landlords on patrol

Other landlords aren’t as open to tenants running their own rental businesses. And some crack down on those who try. Venetia Makshanoff, property operations manager at Mosaic Property Management, said the company has started monitoring Airbnb to see if any apartments within its seven buildings are up for rent.

“We have a gated community, so to speak, and these people are renting to someone that they don’t know and we don’t know and exposing other residents to possible harm,” she said. “We’ve worked hard to put into place what we feel is a fair but stringent screening policy, and people are circumventing that by allowing other people to move in.”

Makshanoff said Mosaic first became aware that some of its tenants were subletting their apartments through the site last summer.

“We did some research and found out that we had three people in Capitol Heights and one in Highland Park using Airbnb, and that’s an absolute violation of our lease,” she said. “We gave them notices to quit (their leases).”

One of the tenants hadn’t yet made her first rental, so Mosaic allowed her to stay, Makshanoff said. But the company issued notices to all of its tenants emphasizing that it prohibited Airbnb rentals.

Cornerstone has taken a similar approach. Hogan said members of his staff check the site about once a month for listings in any of the company’s 107 buildings. If one is discovered, the company notifies the tenant and asks that they resolve the issue within three days – something it has done three times within the past two years.

“If the places are owned, I’m pro-Airbnb,” Hogan said. “I have no qualms with that. But when you’re making money off of someone else’s investment, I have a moral issue with that.”

The city weighs in

Last year, the City Council formed a task force to devise regulations that would allow residents to list their places on Airbnb and other sites if they meet certain criteria. A draft of the proposed regulations calls for zoning code revisions to legalize the practice if the home’s primary resident obtains a business license, affirms that the rental has safety features such as smoke detectors and gets permission from an HOA or landlord if necessary.

The task force, led by Councilwoman Susman, will present the draft at a Neighborhoods and Planning Committee meeting Sept. 2, but it will be months before any regulations are finalized. Palmisano, Susman’s aide, said the council might reach a decision by the end of the year.

The council is also considering imposing the city’s 10.75 percent lodging tax on short-term rentals, an idea backed by the Colorado Hotel and Lodging Association. It’s difficult to quantify Airbnb’s impact on Denver’s hotel industry, but Amie Mayhew, the association’s president, said illicit, tax-free rentals have likely had some effect on revenue.

“We are supportive of regulation and, more importantly, taxing short-term rentals,” Mayhew said. “We’d really like it to be a level playing field.”

Airbnb’s growing popularity doesn’t affect all hotels equally. Researchers at Boston University recently examined Airbnb’s impact on Austin’s hotel industry and found that the city’s mid- and low-priced hotels have lost the most business to the site because some travelers see more value in home sharing at those price points.

Many Denver properties listed on Airbnb for similar prices as midrange hotels are in neighborhoods surrounding the city’s core, such as City Park, where Baute’s studio is located. He said he thinks his renters like to experience parts of the city like a local.

“It gets them into the neighborhoods,” he said. “(My guests) usually ask for the best local restaurants within walking distance. That neighborhood experience is very nice.”

The “regulation” of short term rentals some on Denver City Council are proposing is really a way to “legalize” this activity without neighbors having a say. Under existing Denver Zoning Codes, a short term renter must apply to the zoning administrator for a new Home Occupation permit for rooming/boarding of shorter than 30 days or more than 2 transient occupants and provide notice to their neighbors, registered neighborhood organization and district Council Member. Interested parties can then protest the conversion of a residential property into a hotel in the middle of the neighborhood. The proposed “regulation” avoids this process and automatically makes all residential properties eligible to be converted into a hotel operation by merely applying for a license. This is the type of lax “regulation” airbnb has been lobbying for as it moves towards its $25 billion IPO. Denver Neighborhood Inspection Services has received 60+ specific short term rental complaints and 200+ general home occupation complaints that include STRs in 2015 alone. NIS is just not enforcing the Denver Zoning Codes.