The Buchtel Bungalow, at 2100 S. Columbine St., is owned by the University of Denver. It’s two blocks east of the school’s campus. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

The structure at the southeast corner of Evans and Columbine once housed the third chancellor of the University of Denver, and the 17th governor of Colorado.

In the early 1900s, one man — Henry Buchtel — simultaneously held both posts.

In 1927, Buchtel’s daughter sold what is now known as “Buchtel Bungalow” to DU for $6,000. Over the years, according to the college magazine, the house has been a faculty club, residence hall, fraternity and the residence of the school’s final football coach. DU dropped the sport in the early 1960s. In recent years, it has been “a housing option for DU leadership as they move to Denver,” according to the school.

And on Monday, the structure at 2100 S. Columbine St. became one of 17 structures in the city’s newly created University Park Historic District.

The university, however, didn’t want that to be the case.

“The University, like many other homeowners within the greater University Park neighborhood, is opposed to the inclusion of its property for landmark designation,” Mark DeLorenzo, the university’s senior vice president for business and financial affairs, wrote in a letter to the city last month.

Denver City Council voted 11-0 Monday evening to create the historic district, which covers a small number of properties, largely residences, scattered amidst the blocks east of DU. Councilwomen Sarah Parady and Shontel Lewis.

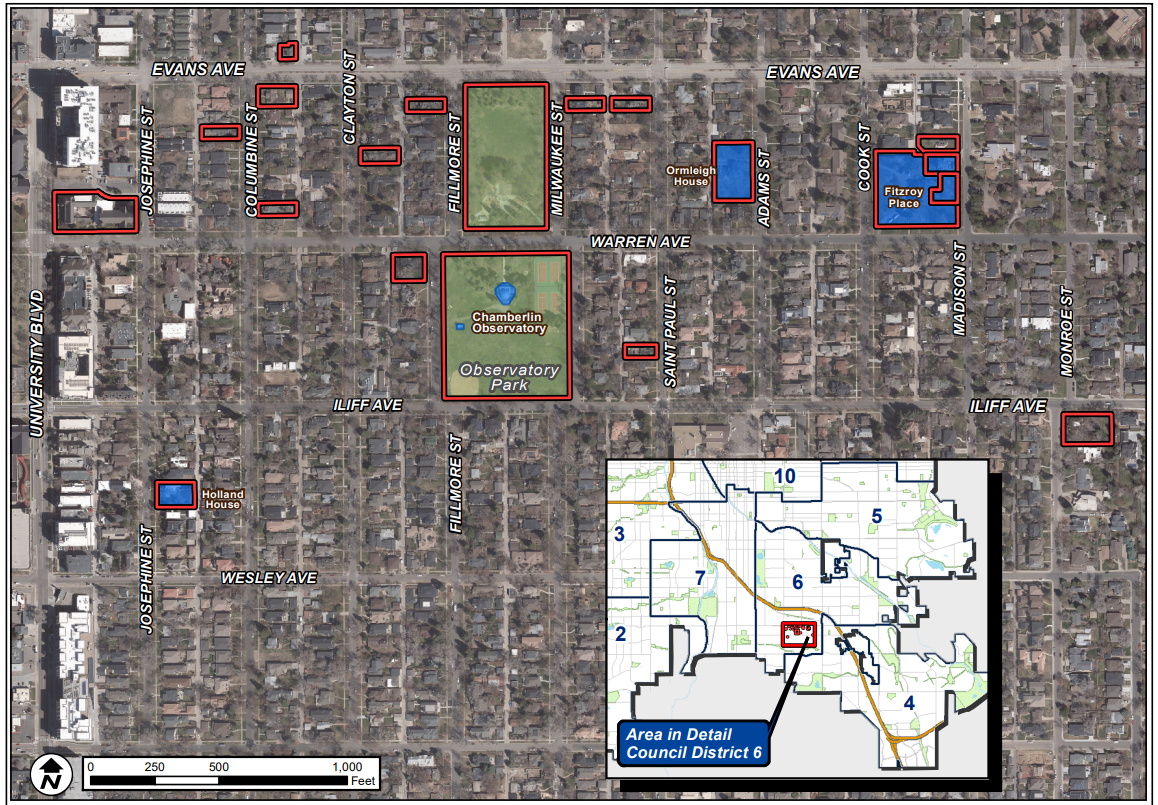

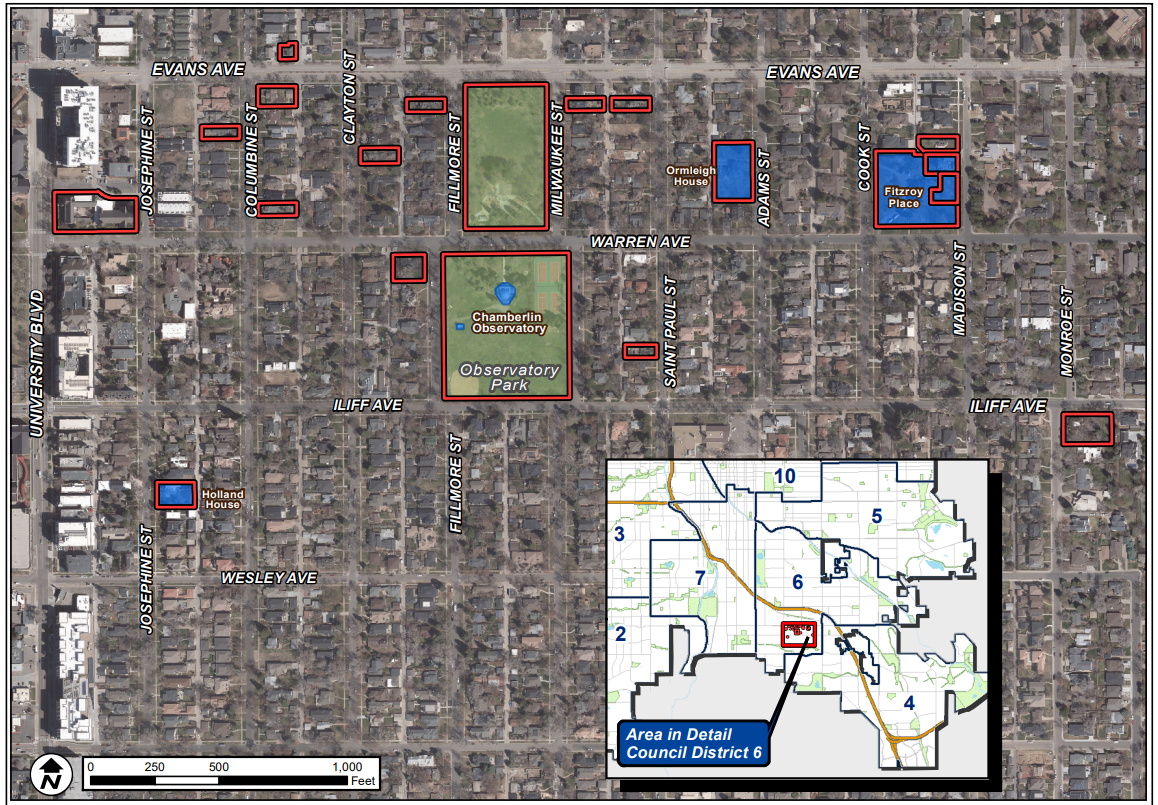

A map showing, in red, the outlines of properties that are part of the University Park Historic District. Blue properties are also individual city landmarks. (City of Denver)

It is the 60th historic district in Denver. That doesn’t count the individual structures around the city that have been designated city landmarks.

Being part of a historic district, or being named an individual landmark, can help property owners secure tax credits or other preservation-focused incentives. But the status also comes with restrictions. Property owners can’t make significant exterior changes to the property without approval of a city commission, which can add time and cost to projects even if approval is granted.

The historic district is only the second in the city — along with the Downtown Denver Historic District — that is not largely contiguous. Councilman Paul Kashmann, who represents the area, said in a meeting last month that the district essentially includes only older properties whose owners were interested — with the exception of DU’s Buchtel Bungalow.

“If people simply didn’t want to be included, they honored that,” Kashmann said.

Proponents generally said the historic district was needed because redevelopment was changing the look of the neighborhood.

“The efforts began when more residents began speaking up about the increasing loss of our neighborhood’s older homes,” the president of the University Park Community Council wrote in a letter to the city.

“We bought this house because we wanted to live in a historic home located in an urban neighborhood with architectural uniqueness and character,” wrote the owner of 2111 S. Fillmore St., which is part of the district.

Fitzroy Place, at 2160 S. Cook St., is part of the new historic district. It was already an individual Denver city landmark. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

The neighborhood’s history largely revolves around DU, which began being developed once the school founded by Methodists moved from downtown in the late 1800s.

“Several strong members of the Methodist community said we should escape the ills and the evils of downtown Denver and move to the purity of the plans south of Denver, six miles south of Denver. And that’s how this property and this neighborhood developed,” said Kara Hahn, who oversees the city’s landmark designation program.

The school was donated land and, after keeping some for its campus, sold off smaller parcels to help fund its operations. Prominent Methodists bought them in an effort to support the school. And what had been plains eventually became urban.

“The University Park Neighborhood and the University of Denver grew up together,” Kashmann said last month. “There’s no way to separate the one from the two.”

DeLorenzo, the DU official, said in his letter last month that the school supported the creation of a historic district, but just didn’t want Buchtel Bungalow included. He noted the school didn’t have an issue with its Chamberlin Observatory building, which is surrounded by Observatory Park, being part of the district. That structure was already an individual city landmark.

But DeLorenzo wrote that the school wants flexibility should it decide to sell Buchtel Bungalow in the future, because DU “does not and cannot utilize the Home for educational purposes.”

“Inclusion in historic/design districts can make it burdensome for homeowners to make simple renovations or improvements … This may be a deterrent to some potential buyers,” he wrote.

The university has considered selling the bungalow before. Robert Coombe, who was the school’s chancellor from 2005 to 2014, told the college magazine in 2007 that the property was on the market when he took the top job and “almost surely would have been demolished by a buyer or developer.” Instead, the college renovated the home and he moved in.

“Our motivation was to save it,” Coombe told the publication in 2007.

The rear of Chamberlin Observatory, which is located within Observatory Park. It is also owned by the University of Denver and part of the new historic district, although it was already an individual city landmark. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

No one from the University of Denver spoke at Monday’s council meeting, which Kashmann said “speaks volumes.”

“I think they missed an opportunity to make a great neighborhood statement,” he said Monday. “That said, I think the university over the years has made many neighborhood statements, so glad to forgive them this one.”

Kashmann said Buchtel Bungalow is “the most historic residence in that neighborhood” and “what’s being asked of the university is the slightest ask that could be presented.”

While being part of a historic district makes it difficult to demolish a structure, Kashmann said the bungalow property isn’t a candidate for redevelopment anyway.

“It is not in a commercial area amidst larger buildings,” he said. “It’s in about a four or five block stretch of just bungalows along Evans Avenue. If a rezoning for that area were proposed during my time on council, I would stand in front of the bulldozers.”

In a statement to BusinessDen on Tuesday, DU said it “respects the process and the decision” made regarding the structure.

“The university is proud of the history of the Buchtel Bungalow and what it has meant to the campus,” the school said.

It’s not unprecedented for property owners to end up in a city historic district against their wishes. A five-year legal fight initiated by some owners within the Packard’s Hill Historic District in West Highland ended in 2022 when the Colorado Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

Denver City Council has also named two properties as individual city landmarks against the wishes of the owner, most recently last year. The property owner in that case, developer Mike Mathieson, subsequently sued the city. The case was paused in late October to allow for a “potential and plausible out of court resolution,” according to court documents. The pause is set to expire later this month.

The Buchtel Bungalow, at 2100 S. Columbine St., is owned by the University of Denver. It’s two blocks east of the school’s campus. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

The structure at the southeast corner of Evans and Columbine once housed the third chancellor of the University of Denver, and the 17th governor of Colorado.

In the early 1900s, one man — Henry Buchtel — simultaneously held both posts.

In 1927, Buchtel’s daughter sold what is now known as “Buchtel Bungalow” to DU for $6,000. Over the years, according to the college magazine, the house has been a faculty club, residence hall, fraternity and the residence of the school’s final football coach. DU dropped the sport in the early 1960s. In recent years, it has been “a housing option for DU leadership as they move to Denver,” according to the school.

And on Monday, the structure at 2100 S. Columbine St. became one of 17 structures in the city’s newly created University Park Historic District.

The university, however, didn’t want that to be the case.

“The University, like many other homeowners within the greater University Park neighborhood, is opposed to the inclusion of its property for landmark designation,” Mark DeLorenzo, the university’s senior vice president for business and financial affairs, wrote in a letter to the city last month.

Denver City Council voted 11-0 Monday evening to create the historic district, which covers a small number of properties, largely residences, scattered amidst the blocks east of DU. Councilwomen Sarah Parady and Shontel Lewis.

A map showing, in red, the outlines of properties that are part of the University Park Historic District. Blue properties are also individual city landmarks. (City of Denver)

It is the 60th historic district in Denver. That doesn’t count the individual structures around the city that have been designated city landmarks.

Being part of a historic district, or being named an individual landmark, can help property owners secure tax credits or other preservation-focused incentives. But the status also comes with restrictions. Property owners can’t make significant exterior changes to the property without approval of a city commission, which can add time and cost to projects even if approval is granted.

The historic district is only the second in the city — along with the Downtown Denver Historic District — that is not largely contiguous. Councilman Paul Kashmann, who represents the area, said in a meeting last month that the district essentially includes only older properties whose owners were interested — with the exception of DU’s Buchtel Bungalow.

“If people simply didn’t want to be included, they honored that,” Kashmann said.

Proponents generally said the historic district was needed because redevelopment was changing the look of the neighborhood.

“The efforts began when more residents began speaking up about the increasing loss of our neighborhood’s older homes,” the president of the University Park Community Council wrote in a letter to the city.

“We bought this house because we wanted to live in a historic home located in an urban neighborhood with architectural uniqueness and character,” wrote the owner of 2111 S. Fillmore St., which is part of the district.

Fitzroy Place, at 2160 S. Cook St., is part of the new historic district. It was already an individual Denver city landmark. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

The neighborhood’s history largely revolves around DU, which began being developed once the school founded by Methodists moved from downtown in the late 1800s.

“Several strong members of the Methodist community said we should escape the ills and the evils of downtown Denver and move to the purity of the plans south of Denver, six miles south of Denver. And that’s how this property and this neighborhood developed,” said Kara Hahn, who oversees the city’s landmark designation program.

The school was donated land and, after keeping some for its campus, sold off smaller parcels to help fund its operations. Prominent Methodists bought them in an effort to support the school. And what had been plains eventually became urban.

“The University Park Neighborhood and the University of Denver grew up together,” Kashmann said last month. “There’s no way to separate the one from the two.”

DeLorenzo, the DU official, said in his letter last month that the school supported the creation of a historic district, but just didn’t want Buchtel Bungalow included. He noted the school didn’t have an issue with its Chamberlin Observatory building, which is surrounded by Observatory Park, being part of the district. That structure was already an individual city landmark.

But DeLorenzo wrote that the school wants flexibility should it decide to sell Buchtel Bungalow in the future, because DU “does not and cannot utilize the Home for educational purposes.”

“Inclusion in historic/design districts can make it burdensome for homeowners to make simple renovations or improvements … This may be a deterrent to some potential buyers,” he wrote.

The university has considered selling the bungalow before. Robert Coombe, who was the school’s chancellor from 2005 to 2014, told the college magazine in 2007 that the property was on the market when he took the top job and “almost surely would have been demolished by a buyer or developer.” Instead, the college renovated the home and he moved in.

“Our motivation was to save it,” Coombe told the publication in 2007.

The rear of Chamberlin Observatory, which is located within Observatory Park. It is also owned by the University of Denver and part of the new historic district, although it was already an individual city landmark. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

No one from the University of Denver spoke at Monday’s council meeting, which Kashmann said “speaks volumes.”

“I think they missed an opportunity to make a great neighborhood statement,” he said Monday. “That said, I think the university over the years has made many neighborhood statements, so glad to forgive them this one.”

Kashmann said Buchtel Bungalow is “the most historic residence in that neighborhood” and “what’s being asked of the university is the slightest ask that could be presented.”

While being part of a historic district makes it difficult to demolish a structure, Kashmann said the bungalow property isn’t a candidate for redevelopment anyway.

“It is not in a commercial area amidst larger buildings,” he said. “It’s in about a four or five block stretch of just bungalows along Evans Avenue. If a rezoning for that area were proposed during my time on council, I would stand in front of the bulldozers.”

In a statement to BusinessDen on Tuesday, DU said it “respects the process and the decision” made regarding the structure.

“The university is proud of the history of the Buchtel Bungalow and what it has meant to the campus,” the school said.

It’s not unprecedented for property owners to end up in a city historic district against their wishes. A five-year legal fight initiated by some owners within the Packard’s Hill Historic District in West Highland ended in 2022 when the Colorado Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

Denver City Council has also named two properties as individual city landmarks against the wishes of the owner, most recently last year. The property owner in that case, developer Mike Mathieson, subsequently sued the city. The case was paused in late October to allow for a “potential and plausible out of court resolution,” according to court documents. The pause is set to expire later this month.