A residential area on the east side of Sloan’s Lake in Denver is seen from the air on March 29, 2020. About one in three property valuation protests were successful in getting a lower value in metro Denver, according to county assessors. Denver residents had a success rate of closer to 45%. (Hyoung Chang/The Denver Post)

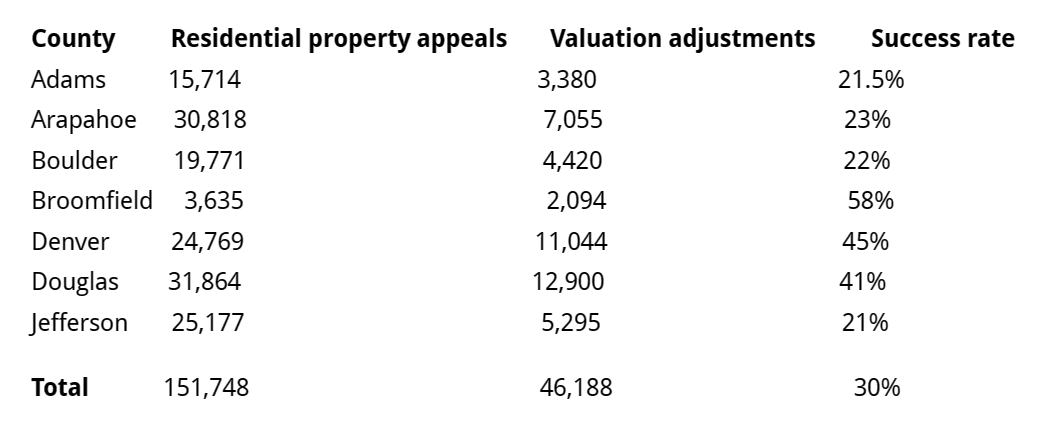

Homeowners in metro Denver and Boulder contested a record number of residential property valuations this year, but county assessors have rejected about seven in 10 of those appeals.

Yet, for homeowners able to win an adjustment, the reductions were substantial, ranging from an average of $43,000 in home value in Adams County to $124,000 in Boulder County, according to a Denver Post analysis of information provided by county assessors.

“This is, by far, the highest appeal rate we’ve ever seen on residential property. The other property classes had average protest rates,” said Douglas County Assessor Toby Damisch. “And it is understandable, as Colorado experienced the largest increase in residential market values in any reappraisal period, which by law had to be reflected in our assessments.”

The share of residential valuation appeals resulting in an adjustment, known as the “success rate,” varied widely by county, from 58% in Broomfield County to between 21% and 23% in Jefferson, Adams, Boulder and Arapahoe counties. About four in 10 appeals resulted in adjustments in Douglas County, while Denver was at 45%.

The success rate of appeals was below that of prior years in most of the counties that provided historical information, although in Broomfield County it went up, from 37% to 58%.

Denver’s success rate held fairly close to the historical average, despite a record volume of residential appeals, which was covered by staff working overtime hours, said Assessor Keith Erffmeyer.

“It is quite possible that more first-timers were doing this because of the volume, but it seems like they listened to the message and directions that got out there,” he said.

But that sentiment was not common across all counties, especially those with a higher rejection rate.

“This year a lot of appeals simply said ‘value is too high’ or ‘I couldn’t sell my house for that price’ with no market support for their claims. A lot of denials are also because of taxpayers not understanding the date of value for the appraisal and providing sales from after the base period,” said Anders Nelson, a spokesman for Arapahoe County.

Providing assessors with comparable sales or comps of neighboring properties to support a lower value is the most common way people protest. But those sales had to have occurred between July 1, 2020, and June 30, 2022.

The temptation to use a sale after the June 30 cutoff was high, given that home values peaked in the spring and fell in the summer and fall because of higher mortgage rates. People weren’t necessarily mistaken in the belief that their homes couldn’t sell any longer for what assessors said they were worth — many just picked the wrong comps to build a case for a lower value, assessors said.

Even those who used proper comps from within the two-year window failed to do something known as “time-trending,” said Thomas Swingle, deputy assessor in Adams County.

Time trending involves taking a sales price earlier in the two-year cycle and bringing it forward to establish an estimated value on July 1, 2022. Some people tried to take lower values from before prices ran up in late 2021 and early 2022 and not adjust them forward, acting as if a record-setting stretch of gains didn’t happen.

“We looked for what would have it sold for on July 1, 2022. If it sold in early 2021, people didn’t time trend it forward,” Swingle said.

Some people mistakenly protested their estimated property taxes rather than their actual property values, given that notices of valuations included a new estimate of property taxes this year.

“Taxes are calculated using assessment rates established by the state legislature and mill levies established by individual taxing jurisdictions. Value is only one part of the formula and it is not in the assessor’s office scope of work to address these parts of the tax calculation,” said Boulder County Assessor Cynthia Braddock.

Erffmeyer said appeals that pointed out characteristics of the property that were wrong in the public record, such as the number of bedrooms or square footage, or regarding the condition of the property, such as a roof that was in need of replacement or a worn out interior, tended to have a higher success rate.

Successful appeals did generate substantial adjustments on average, but the amounts varied by county. Boulder County, given its higher home prices, saw an average adjustment of $124,000 on residential properties. Jefferson County’s adjustments averaged around $80,000.

In Denver, the average adjustment made in the value of residential properties was $47,000, which Erffmeyer said works out to a savings of about $200 a year in property taxes. In Adams County, value reductions averaged $43,000. Douglas County provided its adjustment as a percentage, and that was 7.2% lower.

Property owners in metro Denver who made an appeal should receive notification of the decision this week, along with directions on what to do next if they disagree, either because of a rejection or an inadequate adjustment, Erffmeyer said.

In the state’s more populated counties, appeals can be made to what is known as the County Board of Equalization before Sept. 15, with hearing dates running from Sept. 21 to Oct. 21.

A third party, typically a licensed real estate appraiser, serves as a hearing officer and determines a property’s value after hearing from the property owner and a representative of the county assessor.

“Sometimes a hearing officer can see things differently. It is possible that we didn’t quite catch what property owners were trying to convey,” Erffmeyer said.

Some property owners present the same information again, but their odds improve if they can sharpen their case and provide supplement information, he said. And for those also unhappy with the board’s decision, further avenues of appeal are available, although they involve higher costs and few residential cases make it that far.

This story was originally published by The Denver Post, a BusinessDen news partner.

A residential area on the east side of Sloan’s Lake in Denver is seen from the air on March 29, 2020. About one in three property valuation protests were successful in getting a lower value in metro Denver, according to county assessors. Denver residents had a success rate of closer to 45%. (Hyoung Chang/The Denver Post)

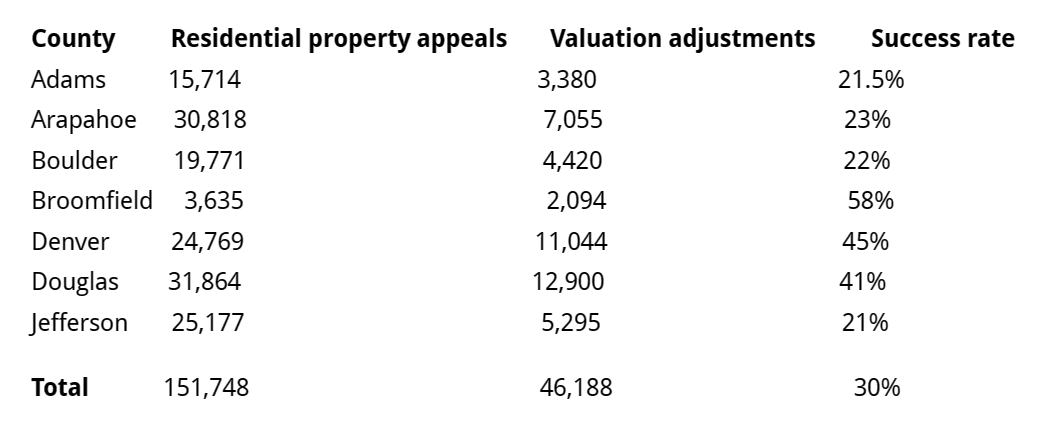

Homeowners in metro Denver and Boulder contested a record number of residential property valuations this year, but county assessors have rejected about seven in 10 of those appeals.

Yet, for homeowners able to win an adjustment, the reductions were substantial, ranging from an average of $43,000 in home value in Adams County to $124,000 in Boulder County, according to a Denver Post analysis of information provided by county assessors.

“This is, by far, the highest appeal rate we’ve ever seen on residential property. The other property classes had average protest rates,” said Douglas County Assessor Toby Damisch. “And it is understandable, as Colorado experienced the largest increase in residential market values in any reappraisal period, which by law had to be reflected in our assessments.”

The share of residential valuation appeals resulting in an adjustment, known as the “success rate,” varied widely by county, from 58% in Broomfield County to between 21% and 23% in Jefferson, Adams, Boulder and Arapahoe counties. About four in 10 appeals resulted in adjustments in Douglas County, while Denver was at 45%.

The success rate of appeals was below that of prior years in most of the counties that provided historical information, although in Broomfield County it went up, from 37% to 58%.

Denver’s success rate held fairly close to the historical average, despite a record volume of residential appeals, which was covered by staff working overtime hours, said Assessor Keith Erffmeyer.

“It is quite possible that more first-timers were doing this because of the volume, but it seems like they listened to the message and directions that got out there,” he said.

But that sentiment was not common across all counties, especially those with a higher rejection rate.

“This year a lot of appeals simply said ‘value is too high’ or ‘I couldn’t sell my house for that price’ with no market support for their claims. A lot of denials are also because of taxpayers not understanding the date of value for the appraisal and providing sales from after the base period,” said Anders Nelson, a spokesman for Arapahoe County.

Providing assessors with comparable sales or comps of neighboring properties to support a lower value is the most common way people protest. But those sales had to have occurred between July 1, 2020, and June 30, 2022.

The temptation to use a sale after the June 30 cutoff was high, given that home values peaked in the spring and fell in the summer and fall because of higher mortgage rates. People weren’t necessarily mistaken in the belief that their homes couldn’t sell any longer for what assessors said they were worth — many just picked the wrong comps to build a case for a lower value, assessors said.

Even those who used proper comps from within the two-year window failed to do something known as “time-trending,” said Thomas Swingle, deputy assessor in Adams County.

Time trending involves taking a sales price earlier in the two-year cycle and bringing it forward to establish an estimated value on July 1, 2022. Some people tried to take lower values from before prices ran up in late 2021 and early 2022 and not adjust them forward, acting as if a record-setting stretch of gains didn’t happen.

“We looked for what would have it sold for on July 1, 2022. If it sold in early 2021, people didn’t time trend it forward,” Swingle said.

Some people mistakenly protested their estimated property taxes rather than their actual property values, given that notices of valuations included a new estimate of property taxes this year.

“Taxes are calculated using assessment rates established by the state legislature and mill levies established by individual taxing jurisdictions. Value is only one part of the formula and it is not in the assessor’s office scope of work to address these parts of the tax calculation,” said Boulder County Assessor Cynthia Braddock.

Erffmeyer said appeals that pointed out characteristics of the property that were wrong in the public record, such as the number of bedrooms or square footage, or regarding the condition of the property, such as a roof that was in need of replacement or a worn out interior, tended to have a higher success rate.

Successful appeals did generate substantial adjustments on average, but the amounts varied by county. Boulder County, given its higher home prices, saw an average adjustment of $124,000 on residential properties. Jefferson County’s adjustments averaged around $80,000.

In Denver, the average adjustment made in the value of residential properties was $47,000, which Erffmeyer said works out to a savings of about $200 a year in property taxes. In Adams County, value reductions averaged $43,000. Douglas County provided its adjustment as a percentage, and that was 7.2% lower.

Property owners in metro Denver who made an appeal should receive notification of the decision this week, along with directions on what to do next if they disagree, either because of a rejection or an inadequate adjustment, Erffmeyer said.

In the state’s more populated counties, appeals can be made to what is known as the County Board of Equalization before Sept. 15, with hearing dates running from Sept. 21 to Oct. 21.

A third party, typically a licensed real estate appraiser, serves as a hearing officer and determines a property’s value after hearing from the property owner and a representative of the county assessor.

“Sometimes a hearing officer can see things differently. It is possible that we didn’t quite catch what property owners were trying to convey,” Erffmeyer said.

Some property owners present the same information again, but their odds improve if they can sharpen their case and provide supplement information, he said. And for those also unhappy with the board’s decision, further avenues of appeal are available, although they involve higher costs and few residential cases make it that far.

This story was originally published by The Denver Post, a BusinessDen news partner.