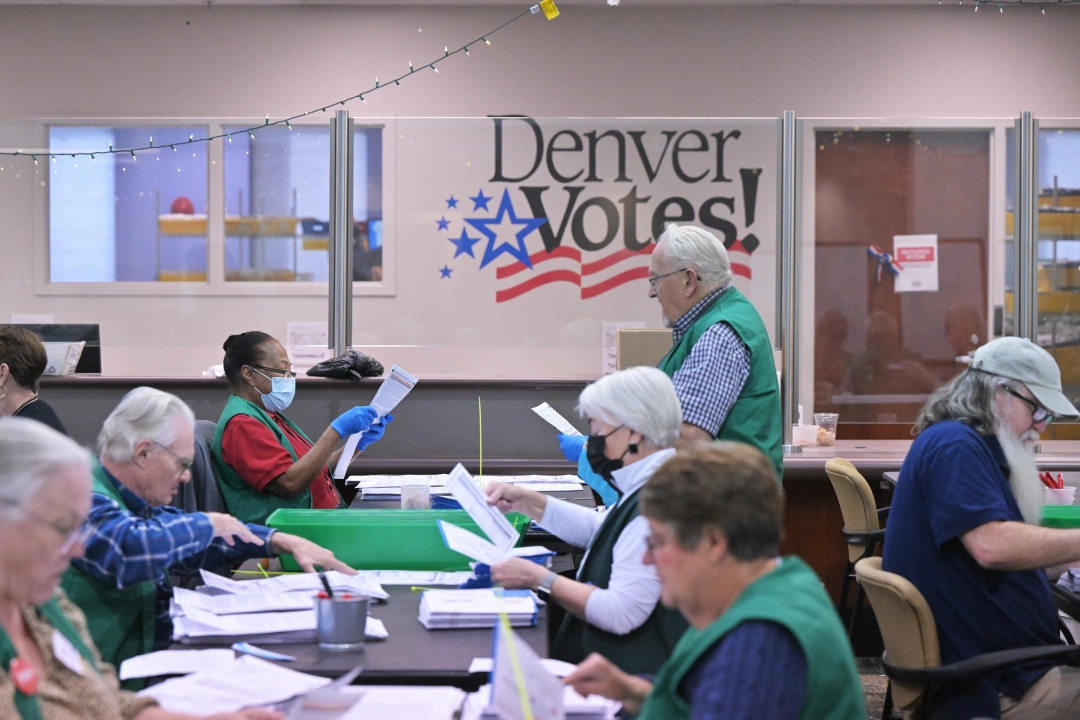

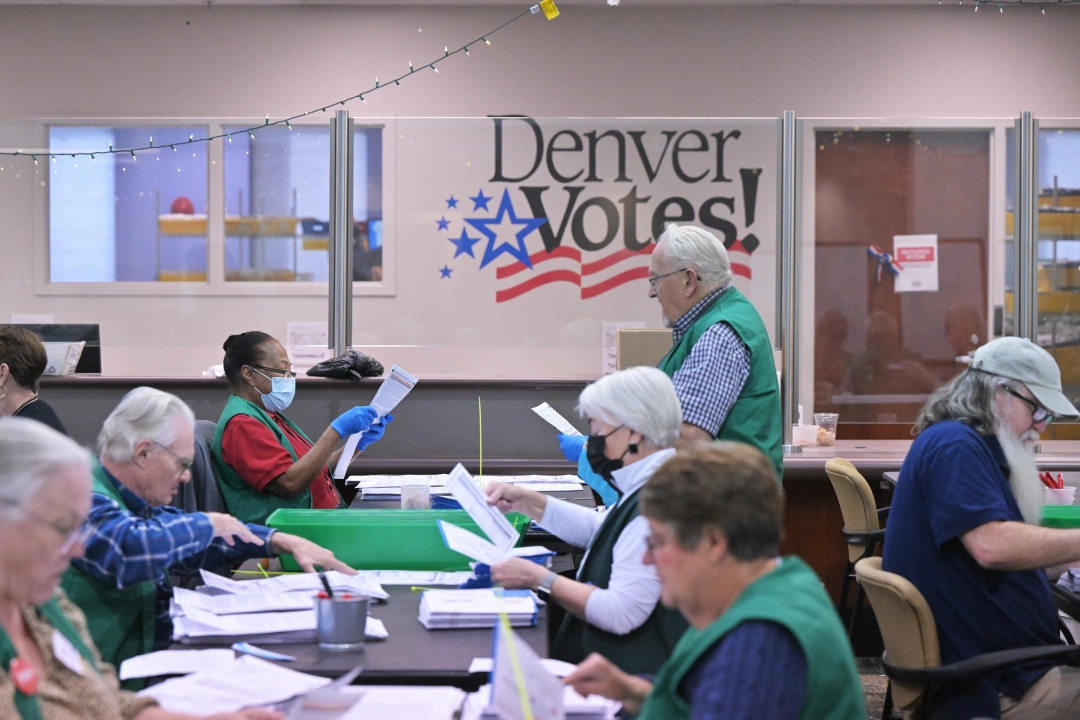

Election judges are sorting ballots at Denver Elections Division in Denver, Colorado on Thursday, Nov. 10, 2022. (Hyoung Chang/The Denver Post)

It took Leslie Herod’s campaign less than 17 hours to collect the 300 verified voter signatures needed to get the mayoral hopeful on the ballot for Denver’s April 4 municipal election.

Being the first candidate to be certified for the ballot could give Herod an edge if she makes it to the runoff stage of the mayor’s race in June. She would be the first name listed above any opponent, an arrangement that research suggests gives a candidate a higher likelihood of winning. With 24 active candidates vying for the mayor’s seat, there is a good chance that no one person will clear 50% of the vote in April, meaning the top two vote-getters will go head-to-head in the runoff.

The speed with which Herod hit the petition mark — turning in her signatures at 4:30 p.m. on the first day gathering was allowed, according to her campaign staff — highlights a concern that has been rumbling beneath the surface of Denver elections: Is it too easy for candidates and citizens’ initiative to get on the ballot?

Petition signature thresholds, both for candidates and for citizen-led initiatives, were listed among “items identified for change” on the Jan. 20, 2022 agenda of the city’s Ballot Access Modernization Committee. But that working group, convened by Denver Clerk and Recorder Paul López and District 4 Councilwoman Kendra Black, never got around to that topic during its five months of work, Black said.

“Signatures could be a working group topic all on its own,” Black said. “The threshold is very low for candidates and very low for ballot measures.”

Instead, the group focused on other changes, like how ballot titles are set for citizens’ initiatives, how the city’s ballot information booklet is constructed and deadlines by which candidates must be certified for the ballot to conform with mail-in voting schedules. Those changes and others were enacted when voters approved Referred Question 2L in November and the City Council passed a companion measure earlier in the year.

Amber McReynolds said the signature topic should be revisited.

“We have over 700,000 people in Denver now so 300 signatures is frankly laughable for mayor,” said McReynolds, an elections expert who served for 13 years as Denver’s director of elections.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimated Denver’s population was around 711,000 people as of July 1. There were 443,600 active, registered voters in the city as of November, according to the Secretary of State’s Office. Gathering 300 signatures means getting support from less than 0.07% of that pool of active voters.

City elections division staff estimated that signature thresholds to run for office in Denver haven’t been adjusted since the 1960s. According to data kept by Boston University, Denver’s population in 1970 was just shy of 515,000, 27% lower than today.

“That number hasn’t been adjusted given our growth,” said McReynolds. “To me, there is an opportunity to look at this in its entirety.”

She favors widescale changes to Denver’s municipal election processes, including increasing signature requirements, doing away with paper petitions in favor of electronic signatures gathering and possibly even moving municipal elections to November to combat voter fatigue.

All told, Herod’s team of about 30 campaign staff members and volunteers collected more than 600 signatures to make sure they were well clear of the 300-signature threshold, she told The Denver Post.

In a December news release, Herod’s team said the city certified 428 signatures from her petitions.

Her team printed petition packets off at home instead of picking them up for the city clerk and recorder’s office on the morning of Dec. 14 as many other campaigns did. They started gathering signatures just after midnight at Charlie’s Nightclub Denver on Colfax Avenue.

“Their karaoke night always draws a great crowd,” Herod said. “Staff and volunteers were then out by 5:30 a.m. talking to people at coffee shops, light rail stations, and breakfast joints across the city.”

Herod may have been the only candidate who turned in her signatures on Dec. 14 but she had plenty of company among candidates who turned petitions in quickly.

By Dec. 15, six more candidates joined her, including mayoral challenger Kelly Brough. By the next afternoon, 28 candidates for various offices had turned in petitions and 11 had been certified for the ballot.

Incumbent District 10 City Councilman Chris Hinds joined Herod as the first in his race to be certified for the ballot, guaranteeing him top-line privileges should the District 10 race go to a runoff. In a news release, Hinds touted being the first council candidate in any district to make the ballot after collecting 220 certified signatures.

Candidates for mayor, auditor, clerk and recorder and city council at-large seats must hit the 300-signature threshold. For district-level council members like Hinds, the total is only 100 so long as the signees live within the district the candidate is seeking to represent. That’s the same number of signatures University of Colorado students must collect from fellow pupils to run for executive seats in student government.

Aside from the possible top-line advantage and having more time to cure any issues that might crop up with a petition, Herod said that being first to turn in signatures is also a demonstration of the enthusiasm around her candidacy and clears the way for more active campaigning.

She would not describe the signature threshold as too low.

“I don’t think it is necessary to second-guess the Denver Charter; our campaign planned to succeed based on what it required,” Herod told the Post. “The fact that none of the other 20-plus candidates for Denver mayor were able to accomplish that on the first day shows that it is not easy. It required hard work, dedication, and the support of a large grassroots network of excited volunteers.”

The way Councilwoman Black remembers it, getting the 100 signatures she needed to get on the ballot to run for District 4 the two times she did so was “pretty effortless.” She is not running for a third term next year and would be in favor of higher candidate signature requirements in the future.

“I think we need to have people who are really serious about this and qualified, and that would just be one safeguard rather than just someone blowing into town and standing at a grocery store and getting signatures and then really impacting who gets into the runoff,” Black said.

As part of the Ballot Access Modernization Committee’s work earlier this year, city staff compiled a list of other major American cities’ requirements to get onto the ballot. They varied widely.

In Baltimore, mayoral candidates don’t need signatures at all, only to pay a $150 fee, per Denver’s research. Meanwhile, Seattle requires mayoral candidates to bring in 600 voters’ signatures accompanied by donations of $10 or more from those signees to their campaign. In San Francisco, mayoral candidates need about 13,000 signatures to get on the ballot or to pay $6,500.

Denver’s creation of a Fair Elections Fund, which provides matching public dollars to qualifying candidates, is another reason to take a hard look at signature thresholds, McReynolds said. There are candidates who have received payments out of the fund who are not yet guaranteed to make it onto the April ballot, she points out.

“I think there is also kind of a timing problem with the process to access the ballot and qualifying for public financing,” McReynolds said. “To me, we shouldn’t be providing funds to people who haven’t qualified for the ballot.”

Owen Perkins, the president of the campaign finance reform-focused organization CleanSlateNow Action, sees no problem with Denver’s current signature thresholds.

Perkins, who led the 2018 campaign for the ballot initiative that created the Fair Elections Fund, said the qualification thresholds built into that program are already a demonstration of candidate seriousness.

The threshold to be able to tap into matching funds for mayoral campaigns is 250 qualifying donations from Denver voters. For a candidate running for any other office, that threshold is 100 qualifying donations, according to the city’s campaign finance manual.

Perkins noted that in 2011, the last time there was no incumbent running for Denver mayor, 20 people filed candidate paperwork. Only 10 of those candidates made the ballot. Three hundred signatures was the same hurdle back then.

“It sounds low to a lot of people. My experience is it’s not easy to get signatures,” he said. “The winnowing down proves it’s not.”

Perkins is looking forward to the April election because he sees a lot of quality candidates in the mayor’s race.

“I think there may be more strong candidates in this field than I have seen before,” he said. “Lots of people who can make claim to ‘front runner’ if not for seven or eight other people also running.”

This story first ran on the Denver Post, a BusinessDen news partner.

Election judges are sorting ballots at Denver Elections Division in Denver, Colorado on Thursday, Nov. 10, 2022. (Hyoung Chang/The Denver Post)

It took Leslie Herod’s campaign less than 17 hours to collect the 300 verified voter signatures needed to get the mayoral hopeful on the ballot for Denver’s April 4 municipal election.

Being the first candidate to be certified for the ballot could give Herod an edge if she makes it to the runoff stage of the mayor’s race in June. She would be the first name listed above any opponent, an arrangement that research suggests gives a candidate a higher likelihood of winning. With 24 active candidates vying for the mayor’s seat, there is a good chance that no one person will clear 50% of the vote in April, meaning the top two vote-getters will go head-to-head in the runoff.

The speed with which Herod hit the petition mark — turning in her signatures at 4:30 p.m. on the first day gathering was allowed, according to her campaign staff — highlights a concern that has been rumbling beneath the surface of Denver elections: Is it too easy for candidates and citizens’ initiative to get on the ballot?

Petition signature thresholds, both for candidates and for citizen-led initiatives, were listed among “items identified for change” on the Jan. 20, 2022 agenda of the city’s Ballot Access Modernization Committee. But that working group, convened by Denver Clerk and Recorder Paul López and District 4 Councilwoman Kendra Black, never got around to that topic during its five months of work, Black said.

“Signatures could be a working group topic all on its own,” Black said. “The threshold is very low for candidates and very low for ballot measures.”

Instead, the group focused on other changes, like how ballot titles are set for citizens’ initiatives, how the city’s ballot information booklet is constructed and deadlines by which candidates must be certified for the ballot to conform with mail-in voting schedules. Those changes and others were enacted when voters approved Referred Question 2L in November and the City Council passed a companion measure earlier in the year.

Amber McReynolds said the signature topic should be revisited.

“We have over 700,000 people in Denver now so 300 signatures is frankly laughable for mayor,” said McReynolds, an elections expert who served for 13 years as Denver’s director of elections.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimated Denver’s population was around 711,000 people as of July 1. There were 443,600 active, registered voters in the city as of November, according to the Secretary of State’s Office. Gathering 300 signatures means getting support from less than 0.07% of that pool of active voters.

City elections division staff estimated that signature thresholds to run for office in Denver haven’t been adjusted since the 1960s. According to data kept by Boston University, Denver’s population in 1970 was just shy of 515,000, 27% lower than today.

“That number hasn’t been adjusted given our growth,” said McReynolds. “To me, there is an opportunity to look at this in its entirety.”

She favors widescale changes to Denver’s municipal election processes, including increasing signature requirements, doing away with paper petitions in favor of electronic signatures gathering and possibly even moving municipal elections to November to combat voter fatigue.

All told, Herod’s team of about 30 campaign staff members and volunteers collected more than 600 signatures to make sure they were well clear of the 300-signature threshold, she told The Denver Post.

In a December news release, Herod’s team said the city certified 428 signatures from her petitions.

Her team printed petition packets off at home instead of picking them up for the city clerk and recorder’s office on the morning of Dec. 14 as many other campaigns did. They started gathering signatures just after midnight at Charlie’s Nightclub Denver on Colfax Avenue.

“Their karaoke night always draws a great crowd,” Herod said. “Staff and volunteers were then out by 5:30 a.m. talking to people at coffee shops, light rail stations, and breakfast joints across the city.”

Herod may have been the only candidate who turned in her signatures on Dec. 14 but she had plenty of company among candidates who turned petitions in quickly.

By Dec. 15, six more candidates joined her, including mayoral challenger Kelly Brough. By the next afternoon, 28 candidates for various offices had turned in petitions and 11 had been certified for the ballot.

Incumbent District 10 City Councilman Chris Hinds joined Herod as the first in his race to be certified for the ballot, guaranteeing him top-line privileges should the District 10 race go to a runoff. In a news release, Hinds touted being the first council candidate in any district to make the ballot after collecting 220 certified signatures.

Candidates for mayor, auditor, clerk and recorder and city council at-large seats must hit the 300-signature threshold. For district-level council members like Hinds, the total is only 100 so long as the signees live within the district the candidate is seeking to represent. That’s the same number of signatures University of Colorado students must collect from fellow pupils to run for executive seats in student government.

Aside from the possible top-line advantage and having more time to cure any issues that might crop up with a petition, Herod said that being first to turn in signatures is also a demonstration of the enthusiasm around her candidacy and clears the way for more active campaigning.

She would not describe the signature threshold as too low.

“I don’t think it is necessary to second-guess the Denver Charter; our campaign planned to succeed based on what it required,” Herod told the Post. “The fact that none of the other 20-plus candidates for Denver mayor were able to accomplish that on the first day shows that it is not easy. It required hard work, dedication, and the support of a large grassroots network of excited volunteers.”

The way Councilwoman Black remembers it, getting the 100 signatures she needed to get on the ballot to run for District 4 the two times she did so was “pretty effortless.” She is not running for a third term next year and would be in favor of higher candidate signature requirements in the future.

“I think we need to have people who are really serious about this and qualified, and that would just be one safeguard rather than just someone blowing into town and standing at a grocery store and getting signatures and then really impacting who gets into the runoff,” Black said.

As part of the Ballot Access Modernization Committee’s work earlier this year, city staff compiled a list of other major American cities’ requirements to get onto the ballot. They varied widely.

In Baltimore, mayoral candidates don’t need signatures at all, only to pay a $150 fee, per Denver’s research. Meanwhile, Seattle requires mayoral candidates to bring in 600 voters’ signatures accompanied by donations of $10 or more from those signees to their campaign. In San Francisco, mayoral candidates need about 13,000 signatures to get on the ballot or to pay $6,500.

Denver’s creation of a Fair Elections Fund, which provides matching public dollars to qualifying candidates, is another reason to take a hard look at signature thresholds, McReynolds said. There are candidates who have received payments out of the fund who are not yet guaranteed to make it onto the April ballot, she points out.

“I think there is also kind of a timing problem with the process to access the ballot and qualifying for public financing,” McReynolds said. “To me, we shouldn’t be providing funds to people who haven’t qualified for the ballot.”

Owen Perkins, the president of the campaign finance reform-focused organization CleanSlateNow Action, sees no problem with Denver’s current signature thresholds.

Perkins, who led the 2018 campaign for the ballot initiative that created the Fair Elections Fund, said the qualification thresholds built into that program are already a demonstration of candidate seriousness.

The threshold to be able to tap into matching funds for mayoral campaigns is 250 qualifying donations from Denver voters. For a candidate running for any other office, that threshold is 100 qualifying donations, according to the city’s campaign finance manual.

Perkins noted that in 2011, the last time there was no incumbent running for Denver mayor, 20 people filed candidate paperwork. Only 10 of those candidates made the ballot. Three hundred signatures was the same hurdle back then.

“It sounds low to a lot of people. My experience is it’s not easy to get signatures,” he said. “The winnowing down proves it’s not.”

Perkins is looking forward to the April election because he sees a lot of quality candidates in the mayor’s race.

“I think there may be more strong candidates in this field than I have seen before,” he said. “Lots of people who can make claim to ‘front runner’ if not for seven or eight other people also running.”

This story first ran on the Denver Post, a BusinessDen news partner.