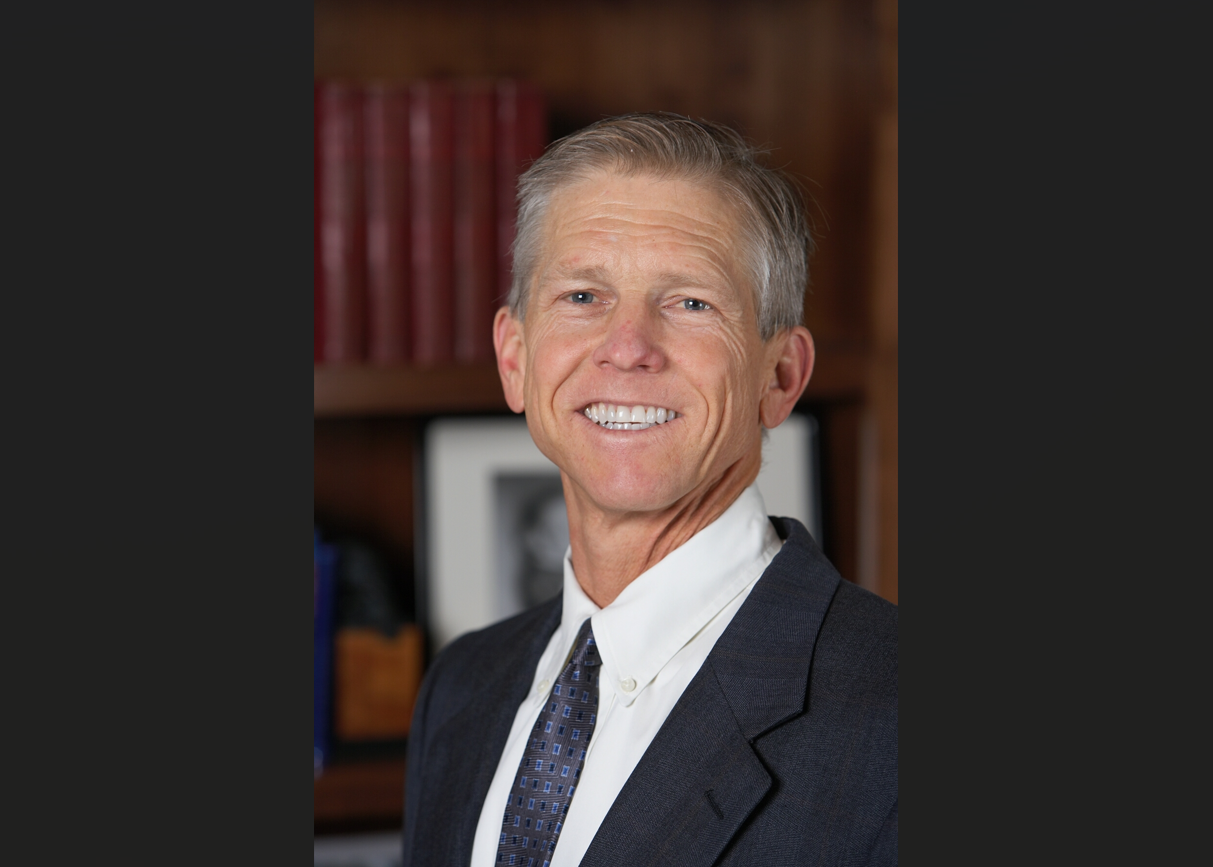

Steve Leonard, whose firm Pacifica Holding Co. bought millions of square feet in the Denver market in the 1990s, has died. (Courtesy Leonard family)

Steve Leonard, an investor who bet big on Denver real estate as the region struggled following the 1980s oil crash, and profited handsomely when he sold nearly everything and moved back to California within a decade, has died.

Leonard was 69. His wife, Cindy, told BusinessDen a “freak accident” caused his death earlier this month.

Leonard graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles in 1977 and in the early 1980s formed Pacifica Holding Co. “to take advantage of commercial real estate cycles,” according to a bio on his company’s website. His father had also worked in real estate.

Leonard began investing in Southern California, where he lived. But before the end of the decade, he’d found a market to go all-in on: Denver. He and Cindy moved to Greenwood Village in 1989, and Leonard, then in his 30s, started buying.

After significant growth in the 1970s and early 1980s, Denver’s economy, heavily reliant on the energy industry, was struggling due to a sharp drop in the price of oil. Property values, both residential and commercial, plummeted. Downtown’s numerous new office buildings failed to fill. The state’s unemployment rate hit 9.1 percent in March 1987, per The Denver Post, well above the national average.

“We were kind of on our butt here, and he came in and started buying property,” said Michael Bloom, an industrial broker and founder of Michael Bloom Realty.

Bloom said Leonard had “a really different look than the old-style suited investment guys.” The first time Bloom met him at Pacifica’s office, Leonard was wearing flip flops.

“He was a young guy, he was very social and he quickly aligned himself with a group of people — brokers mostly,” Bloom said.

“There was no separation of business and friendship with Steve. He always wanted to know who he was transacting with,” said Chetter Latcham, who worked for Leonard and is now president of Shea Homes Colorado.

Leonard largely purchased industrial buildings at first, but added retail and office holdings as the years progressed.

“When we were doing industrial real estate in Denver, we lived it and breathed it to the extent that we knew what was a good value and what wasn’t,” Leonard told an investing newsletter in 2015.

By the third quarter of 1992, Pacifica had bought 3 million square feet across 44 projects with a combined value of about $100 million, according to an article published early the next year in the Rocky Mountain News. Reporter John Rebchook noted the firm was under contract to buy more. And he quoted Brad Neiman, a local broker, saying only somewhat tongue-in-cheek that “contrary to popular theory, Pacifica … will not buy every property offered for sale in 1993.”

Pacifica’s holdings eventually amounted to the largest private commercial portfolio in Colorado, according to another online bio for Leonard.

Leonard wasn’t the only buyer of the assets. Bruce Etkin, who started Etkin Johnson Real Estate Partners with David Johnson in 1989, said there were three main players going after industrial and “office showroom” properties, which combine industrial and office space.

Etkin had a background in construction, but said he began purchasing when “I realized I could buy buildings for 25 percent of what I could build them for.”

Marcel Arsenault’s Colorado & Santa Fe was after volume and “would buy anything,” Etkin said, while Pacifica and Etkin Johnson “competed for the better-quality stuff,” considering factors such as parking ratios.

“He was my competitor from Day 1, until he moved away and sold everything,” Etkin said.

In the final years of Leonard’s time in Denver, Pacifica did some development, according to Latcham, who worked on that side of the business.

“Steve was an investor of conviction. He would do his research and then he would move aggressively,” Latcham said, adding Leonard believed a handshake secured a deal, not the paperwork that followed.

An illustration of Leonard that ran with a 1998 Wall Street Journal story on his decision to exit the Denver market.

By 1997, Leonard believed the Denver market had fully recovered. While others thought it had plenty of room to grow, Leonard told the Wall Street Journal the following year that “trees don’t grow to the sky.”

His firm sold nearly all its local holdings. Mack-Cali Realty Corp. of New Jersey paid $188 million for 1.4 million square feet of office space, according to the Journal. New York’s Kimco Realty Trust bought 630,000 square feet of retail space, and 4.2 million square feet of industrial space went to First Industrial Realty Trust of Chicago.

“It worries me a little bit that Steve thinks it’s the time to sell, and I’m not selling,” Arsenault told the Journal. “I’d sure like him to be doing what I’m doing.”

Leonard continued investing in real estate, primarily in California, after moving back to the state. He also founded Pacifica Capital Investments, which took positions in public companies that Leonard saw as undervalued.

Leonard’s exit from Denver didn’t portend a real estate crash. Etkin Johnson, in fact, took the opposite approach with its holdings, owning them for decades. In 2019, the firm sold 1.95 million industrial square feet for $247.5 million — at the time, the state’s largest industrial deal by both size and price. It eclipsed the mark with a $393 million deal two years later.

“If we felt it was good enough to buy, we felt it was good enough to own forever,” Etkin said, saying he was backed by wealthy individuals who were “investing for their kids” and didn’t pressure him to sell.

Leonard’s Denver era saw the birth of he and his wife’s two children. Both ended up returning to the Front Range as adults. Adi, 31, works for Bow River Capital, based in Cherry Creek. Robert, 28, is a manager and part-owner of 3rd Shot Pickleball in Longmont.

“He would tell us, put all your eggs in one basket, but watch that basket,” Adi said.

Leonard and his wife returned to Colorado regularly, and bought a place in Aspen a dozen years ago, Cindy said. He was competitive, and extremely active across numerous disciplines, from tennis to pickleball to skiing. He did yoga three times a day, according to his daughter.

“He was the most disciplined man I met,” Cindy said.

Leonard was “very passionate about our Constitution, our freedom,” his wife said, adding those wishing to honor his memory can make donations to Young America’s Foundation, which bills itself as “the leading organization for young conservatives.” While in Denver, Leonard founded “Brokers for Battered Kids,” which brought real estate professionals together to compete in various sports for charity.

Leonard was “very much” still working full time at the time of his death, his wife said. And according to industrial broker Bloom, he was growing interested in a new asset: distressed office space. In the wake of the pandemic, downtown Denver’s total office vacancy rate is now above 30 percent. And buildings can be bought for well below their replacement cost.

The last time those things were true, Leonard had just moved to town.

“He was looking at going back into the office space business here,” said Bloom. “I’m not in that world, so I don’t know, but I would have gone in with him.”