Developer Chuck Perry stands in front of the Dry Goods building with Jana Humphries, who manages the building’s income-restricted residential units. (Matt Geiger/BusinessDen)

Last time Chuck Perry redeveloped the Dry Goods building on the 16th Street Mall, the Rockies were playing at Mile High — their temporary home before Coors Field opened in 1995 — and the top song in the nation was Boyz II Men’s “I’ll Make Love to You.”

He finished that project in 1994. Now it’s time for another go at it.

“I never expected in my lifetime to confront the situation that we have here today; I never expected every square foot of retail in this building to be vacant,” said Perry, managing partner of the affordable-minded development firm Perry Rose, referring to the mall-facing portion of the building

Perry, 75, is doubling down on residential. The Dry Goods building already has more than 130,000 square feet of apartments and condos. He plans to fashion another 55 new income-restricted apartments from the building’s existing office and retail space, including part of the T.J. Maxx that closed last January after three decades on the building’s second floor.

The Denver-born-and-raised developer plans to begin construction in 2025 on the project, which was awarded $3.15 million in tax credits in November. And he thinks the rest of the city’s core should be watching.

“I think this building has all of those elements that are key to addressing a lot of the issues that downtown faces,” Perry said.

The Dry Goods building in 1977. (Floyd Patterson/History Colorado)

Once a department store called “The Denver”

On paper, the Dry Goods building is an imposing six-story, roughly 330,000-square-foot rectangle taking up half a city block in Upper Downtown. It runs along California Street between 15th and 16th streets.

The oldest part of the structure dates to 1888, when it was just three stories on about a quarter of the block. Frank D. Edbrooks, the building’s architect, is credited with helping design a number of Denver’s most prominent structures, including the State Capitol and Brown Palace Hotel.

Additions to the building over the next 40 years brought it to its size today. By the mid-1910s, it had become the nation’s largest department store west of Chicago, according to Perry.

Back then, the building was known as “The Denver” to most locals. It was the everything store, offering fine dining and shopping, and saddles for cowboys. Perry recalls visiting the store when he was in junior high in the 1960s, spending time with his aunt in the Tea Room on the fifth floor.

But the store suffered as downtown hollowed out in the 1970s. In 1987, the property was purchased by The May Department Stores Co., which closed the store the following month. Downtown was suffering amidst the oil bust.

Demolition of the Dry Goods building became a real possibility. No private buyers were interested.

In the 1990s, a “rooftops precede retail” redevelopment strategy

As a last-ditch effort to save the building, the city, through the Denver Urban Renewal Authority, acquired the building in July 1988 for $6.9 million, according to a Urban Land case study on the redevelopment. That’s equivalent to about $17.8 million today.

Perry worked as the assistant executive director for DURA at the time. He previously had been an urban planner with the city.

For two years, developers submitted various adaptive reuse proposals to DURA. Options ranged from an aquarium to hotels and upscale housing. Others suggested movie theaters and a retail mall, but none of the pitches met financing or leasing requirements, per the case study.

“One of the problems with all of the previous development proposals that had failed was that they tried to take a 350,000-square-foot building and redevelop it in one big chunk. And the market was terrible, so you couldn’t finance it, which is the case again today,” Perry said.

But Jonathan Rose — a New York City developer at the time, and now Perry’s business partner — saw opportunity.

“His (Rose’s) two key contributions to solving the problem, were number one, to identify affordable housing as the key component to the menu of redevelopment options, and to recognize that you need to phase the development,” Perry said.

Using 23 different financing sources, Rose, Perry and the city teamed up to tackle the herculean task of reimagining the space. The total cost of the project was $48 million.

Dry Goods building undergoing redevelopment in 1993. Over 30 layers of lead-based white paint were removed to showcase the building’s original facade. The removal and subsequent repairs cost $800,000 and took eight months to complete, per a case study on the project. (Courtesy of Denver Public Library Digital Collections/History Colorado)

Perry said they imagined the building as two separate structures, with smaller divisions within them. This allowed for multiple uses within the building, with retail and office space below and apartments above.

The project was completed in 1994. At the time, the retail tenants on the ground floor and basement were Media Play, a Blockbuster-type video store, and Waxman’s Camera and Video. Up on the second floor were T.J. Maxx and new offices for DURA. Visit Denver took office space on the third floor.

“The T.J. Maxx that was here was modeled after the T.J. Maxx on State Street in Chicago, which is on the second floor and has an escalator up (to the entrance),” Perry said.

The remaining three-and-a-half stories were split between 65 market-rate apartments and 51 income-restricted units.

“There are 20 other projects in downtown that are developed based on this (Dry Goods redevelopment) model,” Perry said.

That model, he explained, is leveraging public funds such as historic and low-income housing tax credits, along with tax-increment financing, to help construct affordable housing.

“Rooftops precede retail. And so if you’re ever going to have retail downtown, you got to have some people that live downtown that will shop downtown. And the first place to start doing that is with affordable housing,” Perry said.

Chuck Perry looks at a historic photo displayed in the Dry Goods building. (Matt Geiger/BusinessDen)

Redevelopment round two: Even more rooftops

After the redevelopment was completed, Perry and Rose went into business together, starting Perry Rose. That firm will help oversee the redevelopment of the property this time around.

As it stands now, the Dry Goods Building features a 10,000-square-foot Ruth’s Chris Steak House and a 6,000-square-foot health clinic on the ground floor facing California Street. There’s 30,000 square feet of offices — still occupied by DURA and Visit Denver — as well as 77,000 square feet of market-rate apartments and condos, 60,000 square feet of income-restricted units and 43,000 square feet of common areas.

There’s also approximately 104,000 square feet of vacant retail space, most notably the former T.J. Maxx.

Visit Denver will move its offices across the street. DURA also plans to move out. Their space, along with much of the vacant retail, will then be converted into residences and amenities for those who live in the building.

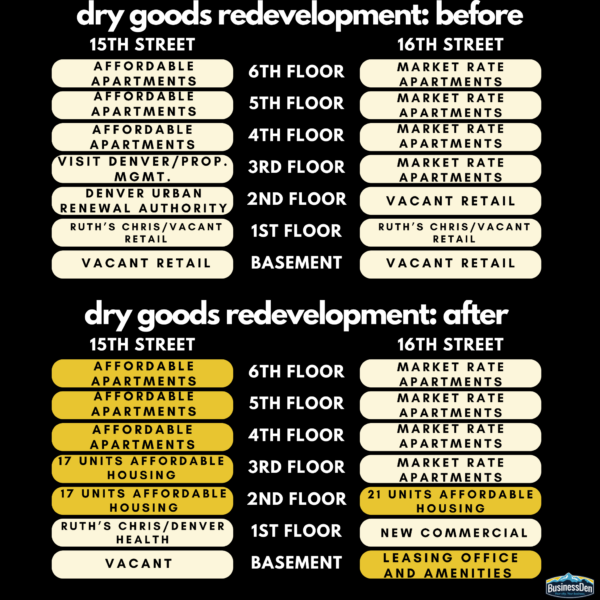

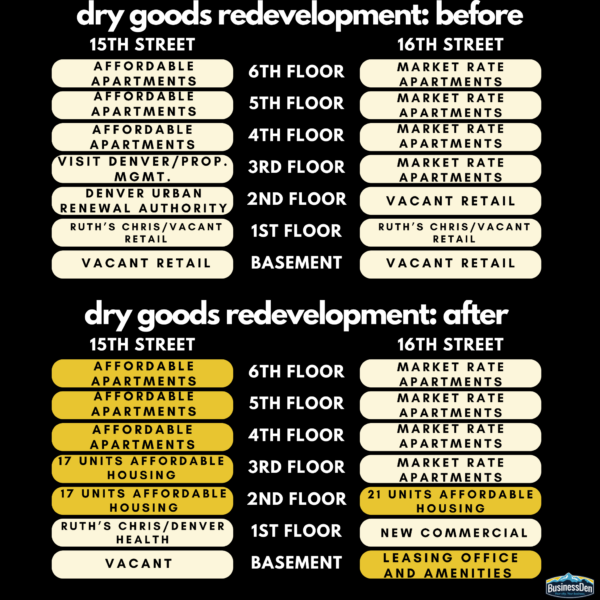

Current and proposed post-redevelopment uses of the floors within the Dry Goods building. (Graphic by BusinessDen)

Besides constructing 55 new income-restricted units, plans call for the renovation of the existing 51 income-restricted apartments and converting the building from outdated steam heating to a more modern hybrid gas and electric system.

The 106 affordable units will be divided into 66 one-bedroom and 40 two-bedroom apartments, reserved for those making up to 30 percent and 80 percent of the area median income. Some apartments feature 16-foot tall ceilings and fantastic views of downtown.

“One of the great things about this building is its windows,” Perry said.

The view from one of the building’s income-restricted apartments. (Matt Geiger/BusinessDen)

The basement will be remodeled to include amenities for tenants, such as a gym, pantry, supportive services, coworking space, mailroom and leasing office.

Jana Humphries, who oversees the day-to-day operations of the affordable housing, said the first redevelopment was “cutting edge” at the time.

“The way that Chuck has always described this building was that it was a catalyst in the change,” she said. “The original blight of downtown was turned around in large part because of this building.”

While the building, and downtown, again face challenges, Humphries sees plenty of reasons to be more optimistic this time around.

“The transit used to be the RTD bus. We now have a light rail stop. We did not have a convention center a block from us. We now have a convention center a block from us,” she said. “There are more elements that are even more in our favor now than back then.”

But while Perry is confident in his plan for the Dry Goods Building, the path forward for broader downtown isn’t so certain, he said.

“I don’t think the path is exactly clear. And so what we need is some real visionary leaders and some real visionary planners, and we need to bridge the divisiveness that our society is subject to,” Perry said.

Developer Chuck Perry stands in front of the Dry Goods building with Jana Humphries, who manages the building’s income-restricted residential units. (Matt Geiger/BusinessDen)

Last time Chuck Perry redeveloped the Dry Goods building on the 16th Street Mall, the Rockies were playing at Mile High — their temporary home before Coors Field opened in 1995 — and the top song in the nation was Boyz II Men’s “I’ll Make Love to You.”

He finished that project in 1994. Now it’s time for another go at it.

“I never expected in my lifetime to confront the situation that we have here today; I never expected every square foot of retail in this building to be vacant,” said Perry, managing partner of the affordable-minded development firm Perry Rose, referring to the mall-facing portion of the building

Perry, 75, is doubling down on residential. The Dry Goods building already has more than 130,000 square feet of apartments and condos. He plans to fashion another 55 new income-restricted apartments from the building’s existing office and retail space, including part of the T.J. Maxx that closed last January after three decades on the building’s second floor.

The Denver-born-and-raised developer plans to begin construction in 2025 on the project, which was awarded $3.15 million in tax credits in November. And he thinks the rest of the city’s core should be watching.

“I think this building has all of those elements that are key to addressing a lot of the issues that downtown faces,” Perry said.

The Dry Goods building in 1977. (Floyd Patterson/History Colorado)

Once a department store called “The Denver”

On paper, the Dry Goods building is an imposing six-story, roughly 330,000-square-foot rectangle taking up half a city block in Upper Downtown. It runs along California Street between 15th and 16th streets.

The oldest part of the structure dates to 1888, when it was just three stories on about a quarter of the block. Frank D. Edbrooks, the building’s architect, is credited with helping design a number of Denver’s most prominent structures, including the State Capitol and Brown Palace Hotel.

Additions to the building over the next 40 years brought it to its size today. By the mid-1910s, it had become the nation’s largest department store west of Chicago, according to Perry.

Back then, the building was known as “The Denver” to most locals. It was the everything store, offering fine dining and shopping, and saddles for cowboys. Perry recalls visiting the store when he was in junior high in the 1960s, spending time with his aunt in the Tea Room on the fifth floor.

But the store suffered as downtown hollowed out in the 1970s. In 1987, the property was purchased by The May Department Stores Co., which closed the store the following month. Downtown was suffering amidst the oil bust.

Demolition of the Dry Goods building became a real possibility. No private buyers were interested.

In the 1990s, a “rooftops precede retail” redevelopment strategy

As a last-ditch effort to save the building, the city, through the Denver Urban Renewal Authority, acquired the building in July 1988 for $6.9 million, according to a Urban Land case study on the redevelopment. That’s equivalent to about $17.8 million today.

Perry worked as the assistant executive director for DURA at the time. He previously had been an urban planner with the city.

For two years, developers submitted various adaptive reuse proposals to DURA. Options ranged from an aquarium to hotels and upscale housing. Others suggested movie theaters and a retail mall, but none of the pitches met financing or leasing requirements, per the case study.

“One of the problems with all of the previous development proposals that had failed was that they tried to take a 350,000-square-foot building and redevelop it in one big chunk. And the market was terrible, so you couldn’t finance it, which is the case again today,” Perry said.

But Jonathan Rose — a New York City developer at the time, and now Perry’s business partner — saw opportunity.

“His (Rose’s) two key contributions to solving the problem, were number one, to identify affordable housing as the key component to the menu of redevelopment options, and to recognize that you need to phase the development,” Perry said.

Using 23 different financing sources, Rose, Perry and the city teamed up to tackle the herculean task of reimagining the space. The total cost of the project was $48 million.

Dry Goods building undergoing redevelopment in 1993. Over 30 layers of lead-based white paint were removed to showcase the building’s original facade. The removal and subsequent repairs cost $800,000 and took eight months to complete, per a case study on the project. (Courtesy of Denver Public Library Digital Collections/History Colorado)

Perry said they imagined the building as two separate structures, with smaller divisions within them. This allowed for multiple uses within the building, with retail and office space below and apartments above.

The project was completed in 1994. At the time, the retail tenants on the ground floor and basement were Media Play, a Blockbuster-type video store, and Waxman’s Camera and Video. Up on the second floor were T.J. Maxx and new offices for DURA. Visit Denver took office space on the third floor.

“The T.J. Maxx that was here was modeled after the T.J. Maxx on State Street in Chicago, which is on the second floor and has an escalator up (to the entrance),” Perry said.

The remaining three-and-a-half stories were split between 65 market-rate apartments and 51 income-restricted units.

“There are 20 other projects in downtown that are developed based on this (Dry Goods redevelopment) model,” Perry said.

That model, he explained, is leveraging public funds such as historic and low-income housing tax credits, along with tax-increment financing, to help construct affordable housing.

“Rooftops precede retail. And so if you’re ever going to have retail downtown, you got to have some people that live downtown that will shop downtown. And the first place to start doing that is with affordable housing,” Perry said.

Chuck Perry looks at a historic photo displayed in the Dry Goods building. (Matt Geiger/BusinessDen)

Redevelopment round two: Even more rooftops

After the redevelopment was completed, Perry and Rose went into business together, starting Perry Rose. That firm will help oversee the redevelopment of the property this time around.

As it stands now, the Dry Goods Building features a 10,000-square-foot Ruth’s Chris Steak House and a 6,000-square-foot health clinic on the ground floor facing California Street. There’s 30,000 square feet of offices — still occupied by DURA and Visit Denver — as well as 77,000 square feet of market-rate apartments and condos, 60,000 square feet of income-restricted units and 43,000 square feet of common areas.

There’s also approximately 104,000 square feet of vacant retail space, most notably the former T.J. Maxx.

Visit Denver will move its offices across the street. DURA also plans to move out. Their space, along with much of the vacant retail, will then be converted into residences and amenities for those who live in the building.

Current and proposed post-redevelopment uses of the floors within the Dry Goods building. (Graphic by BusinessDen)

Besides constructing 55 new income-restricted units, plans call for the renovation of the existing 51 income-restricted apartments and converting the building from outdated steam heating to a more modern hybrid gas and electric system.

The 106 affordable units will be divided into 66 one-bedroom and 40 two-bedroom apartments, reserved for those making up to 30 percent and 80 percent of the area median income. Some apartments feature 16-foot tall ceilings and fantastic views of downtown.

“One of the great things about this building is its windows,” Perry said.

The view from one of the building’s income-restricted apartments. (Matt Geiger/BusinessDen)

The basement will be remodeled to include amenities for tenants, such as a gym, pantry, supportive services, coworking space, mailroom and leasing office.

Jana Humphries, who oversees the day-to-day operations of the affordable housing, said the first redevelopment was “cutting edge” at the time.

“The way that Chuck has always described this building was that it was a catalyst in the change,” she said. “The original blight of downtown was turned around in large part because of this building.”

While the building, and downtown, again face challenges, Humphries sees plenty of reasons to be more optimistic this time around.

“The transit used to be the RTD bus. We now have a light rail stop. We did not have a convention center a block from us. We now have a convention center a block from us,” she said. “There are more elements that are even more in our favor now than back then.”

But while Perry is confident in his plan for the Dry Goods Building, the path forward for broader downtown isn’t so certain, he said.

“I don’t think the path is exactly clear. And so what we need is some real visionary leaders and some real visionary planners, and we need to bridge the divisiveness that our society is subject to,” Perry said.