Rad Power Bikes’ store at 3869 Steele St. in Denver. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

Two years into a program that helps Denverites pay for an electric bike, one company has consistently dominated the market.

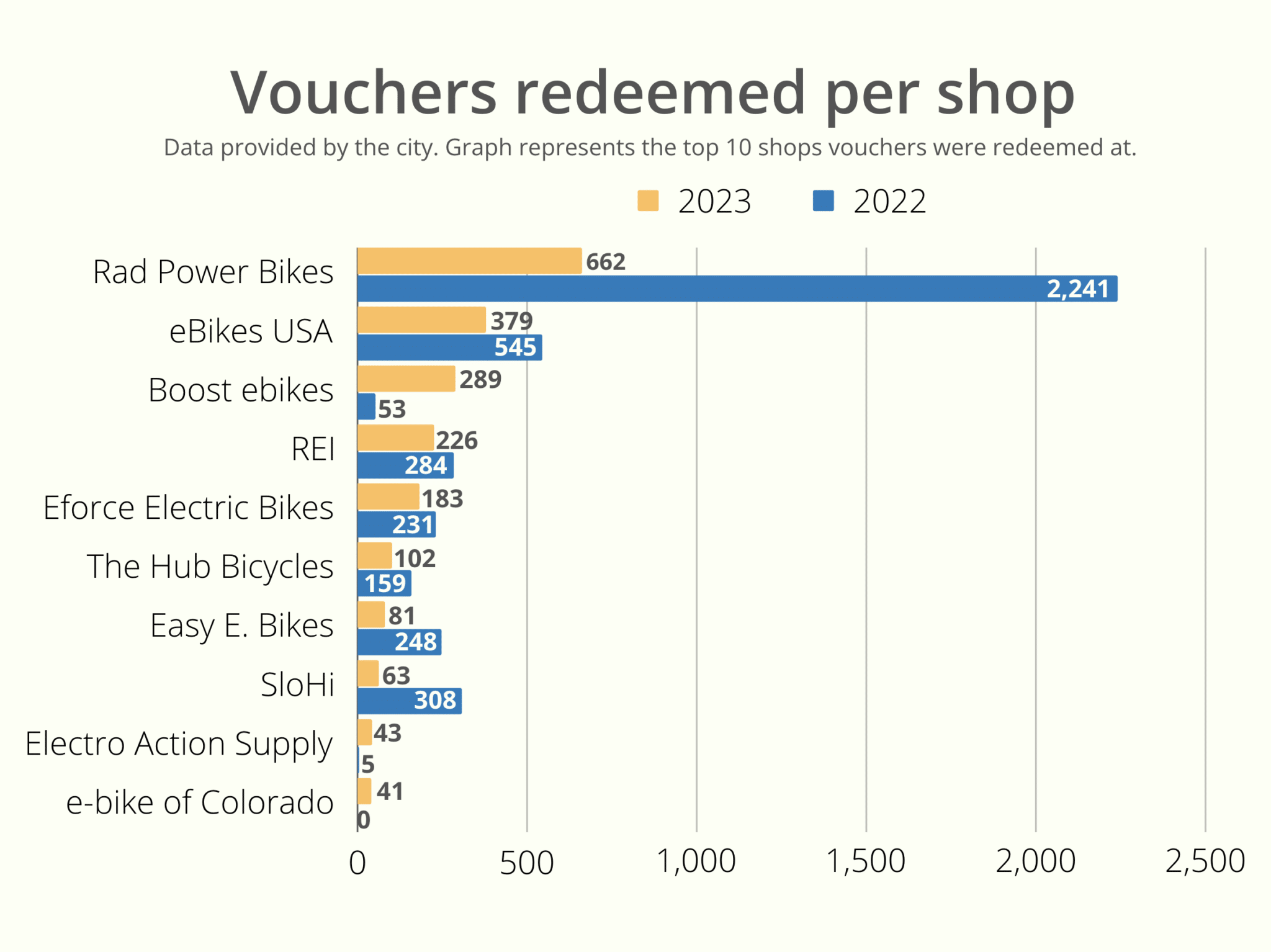

Seattle-based Rad Power Bikes, which sells bikes around $1,400, claimed 27 percent of e-bike vouchers redeemed this year and 47 percent last year — far more than any other participating shop.

In June, the company told Colorado Public Radio, which also highlighted Rad’s voucher results, that it always planned to open a store in Denver but accelerated those plans so it could participate in the program.

Rad’s high voucher sales left some local shop owners with mixed feelings.

“I have people coming into my store and saying I have a $1,100 voucher, I need a $1,100 bike,” said Kenny Fischer, owner of FattE Bikes in Sun Valley. “Nobody can compete with free. If a person has never ridden or owned an e-bike before, they don’t care if it’s junk or not, it’s free.”

“The City of Denver, they’re doing what they were tasked to do: put more consumers on electric bikes,” said Houshmand Moarefi, owner of eBikes USA in Cherry Creek “And boy did they succeed, but along the way they changed the marketplace.”

Denver launched the rebate program last year. Depending on their income, Denver residents can receive vouchers between $300 and $1,400 to put toward the purchase of an e-bike.

Nearly 4,750 vouchers were redeemed last year, and 2,386 had been redeemed as of Oct. 31, according to the city. The number of vouchers is lower this year because the program’s budget is smaller than in 2022, and some have yet to be redeemed. This year’s final set of vouchers will be issued later this month.

A graph of voucher redemptions by top 10 shops in 2022 and so far in 2023. (Data from City of Denver; graph by BusinessDen)

Emily Gedeon, spokeswoman for Denver’s Office of Climate Action, Sustainability and Resiliency, said vouchers can be used only at approved shops, which must have a brick-and-mortar location in the Denver area and be able to service a bike.

“Ultimately, once we distribute the voucher it’s up to the customer to select which e-bike fits their budget, comfort and safety level and best aligns with what they need to get around town,” she said.

Gedeon said the city has been surveying voucher users to help evaluate the program moving forward. City staff also met with 15 shop owners last month to hear their feedback.

Houshmand Moarefi of eBikes USA

Moarefi, with eBikes USA, said he’s done well because of the rebate program. Last year, Moarefi sold 545 bikes to someone using a voucher. This year he’s at about 380.

“We’re still number two in this program, but we had to really work hard at it,” Moarefi said. “I was seeing a trend earlier in the year that I frankly didn’t like … We had to change our business practice in order to remain relevant in today’s market.”

He said after national chains opened in Denver to capitalize on the program, the costs of e-bikes plummeted. With a large company like Rad selling bikes for around $1,400, he said, many customers weren’t willing to buy one at a local shop for more.

“The psyche of the consumer changed because there were lower-cost bikes,” Moarefi said. “I welcome competition, so I’m not going to say kick the national brands out. I think the market will decide where they want to spend their money.”

To keep up with the new competition, Moarefi said he started offering less-expensive bikes and price matching with other brands online.

“There is a cost to this shift,” he said. “In order for us to match the revenue dollars of last year … we have to sell more bikes that have lower average prices. Our operational overhead has gone up because of this, but our margins have gone down.”

And he doesn’t anticipate this will be the only change he has to make. Given that the state now has its own rebate program, which launched in August, Moarefi said he thinks the market will be entirely different next year.

Moarefi said he’s considering other changes like expanding the bike maintenance portion of his business, or moving out of pricey Cherry Creek.

Kenny Fischer of FattE-Bikes

Fischer, of FattE-Bikes — which manufactures its bikes and doesn’t sell other brands— took a different path.

After seeing the number of vouchers redeemed at his store plummet this year compared to last — 200 in 2022 and 31 this year, per the city, Fischer is changing his business model. He told BusinessDen last month he’ll stop selling direct-to-consumer by the end of the year in favor of fleet sales.

“If I don’t change, something is going to happen,” Fischer said. “It’s unfortunate because it’s our local customer who we can support the most and can appreciate what we do.”

Fischer said if the city were to change the structure of the voucher, like setting it at $500 instead of the sliding scale, it would likely bring more business back to local shops.

“Everybody is always watching Denver … we’re thought leaders in this country,” he said. “This is going to be a national problem putting a lot of local bike shops at risk.”

Although he understands the city’s perspective, Fischer said it is “myopic” and not taking into account the negative impacts the program has had on local shops.

“All the money is now getting pumped out of state,” Fischer said. “The city and state (initiative) is to get as many rebates out there and not necessarily concerned with where they’re going and what the results a year from now will be.”

MacKenzie Hardt of Hardt Family Cyclery

MacKenzie Hardt, owner of Hardt Family Cyclery in Aurora, echoed a similar sentiment.

“Most of our money went out of state and overseas,” Hardt said. “That’s unfortunate, those tax dollars don’t stay here.”

But Hardt said the dynamic isn’t impacting his business, which like eBikes USA sells a number of brands. He specializes in high-end e-bikes that range from a couple thousand dollars to $11,000 and are intended to fully replace a car. Hardt had 92 vouchers redeemed at his store last year and 31 this year.

“Without the rebate, I don’t think our sales would’ve been lower,” he said.

But as a former director of a nonprofit that advocated for bike accessibility, safety and education, Hardt takes issue with the lack of safety standards for shops participating in the rebate program.

“It’s the safety concerns I’m trying to get people to pay attention to,” Hardt said. “Locals have worked hard to make sure they’re putting out products that are safe.”

Rad Power Bikes has been sued a handful of times in recent years over claims such as faulty manufacturing. Last November, the company recalled one of its cargo bikes because of tires unexpectedly deflating, causing serious crashes.

“As an industry innovator and leader in e-bikes, Rad Power Bikes holds the safety of our riders as our top priority,” a Rad Power Bikes spokesperson said. “We design our e-bikes and accessories, including the brakes and batteries, to exceed safety and quality standards.”

After an increase of deadly fires related to lithium batteries, New York City passed a law in September that requires e-bike and scooter batteries to be certified by UL, an American company known for testing and setting safety standards in electronics.

Hardt thinks Denver should do something similar, especially for voucher-approved shops. In addition, he said e-bike stores should be required to have licensed mechanics based in the shop assembling the bikes.

Rad announced last week it’s closing its New York City location, but said it would start adhering to UL standards nationwide.

Moarefi agreed that safety should be at the forefront of Denver’s program, and Fischer noted that eliminating cheaply made bikes, like Rad’s, would solve a lot of safety issues. All three shop owners attended Denver’s meeting last month to voice their concerns.

“I am happy now that they’re listening and pivoting, but we have to wait and see what hard decisions and regulations they make,” Hardt said.