Downtown Denver looms in the background as a truck rumbles north in Fox Island, a 185-acre neighborhood surrounded by interstates and railroad tracks. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

Editor’s note: This is the first half of a two-part series. To read Part 2, click the link: “Island tripping: Denver’s plan to relieve restriction hinges on private developers”

They call it Fox Island.

It’s a 185-acre pocket of Denver, technically part of Globeville, surrounded not by water but by transportation corridors — Interstate 70 to the north, Interstate 25 to the east and south, and railroad tracks to the west.

Fox Street is the one main road that traverses it.

“It really is an island,” said Chris Nevitt, Denver’s manager for transit-oriented development. “The street grid does not penetrate it at all, except for two spots.”

In 2019, the neighborhood got an RTD rail station, known as 41st and Fox. That effectively ensured that the largely industrial neighborhood, which also has a smattering of older homes, would become a hot spot for redevelopment, particularly new housing.

And that is indeed happening — to the extent that the City of Denver allows it.

If you own a property in Fox Island today, it’s unlikely you can get a developer to buy it.

Russell Gruber, a commercial real estate broker, has been marketing industrial properties in the neighborhood for 16 years. He estimates he knows 85 percent of the owners.

But the head of Gruber Commercial Real Estate said he’s now turning down business there.

“I’m literally passing on listings in this neighborhood,” he said. “Because there’s been nothing I can do for them. I’ll just put up a sign.”

It’s a result of an only-in-Fox-Island restriction: the trip cap.

City rules implemented in 2018 mean developers can build something in Fox Island only if they are allotted a certain number of “trips.” The number is meant to correspond to how much additional vehicle traffic their project will add to the area.

No other part of Denver has a similar restriction. And, from the start, because of the limited access points, the number of trips that could be claimed was capped. So while the rules have been in place for five years, a key thing happened in 2023 in Fox Island, which still has a host of undeveloped and underutilized lots.

“We have used up all the available trips,” Nevitt said.

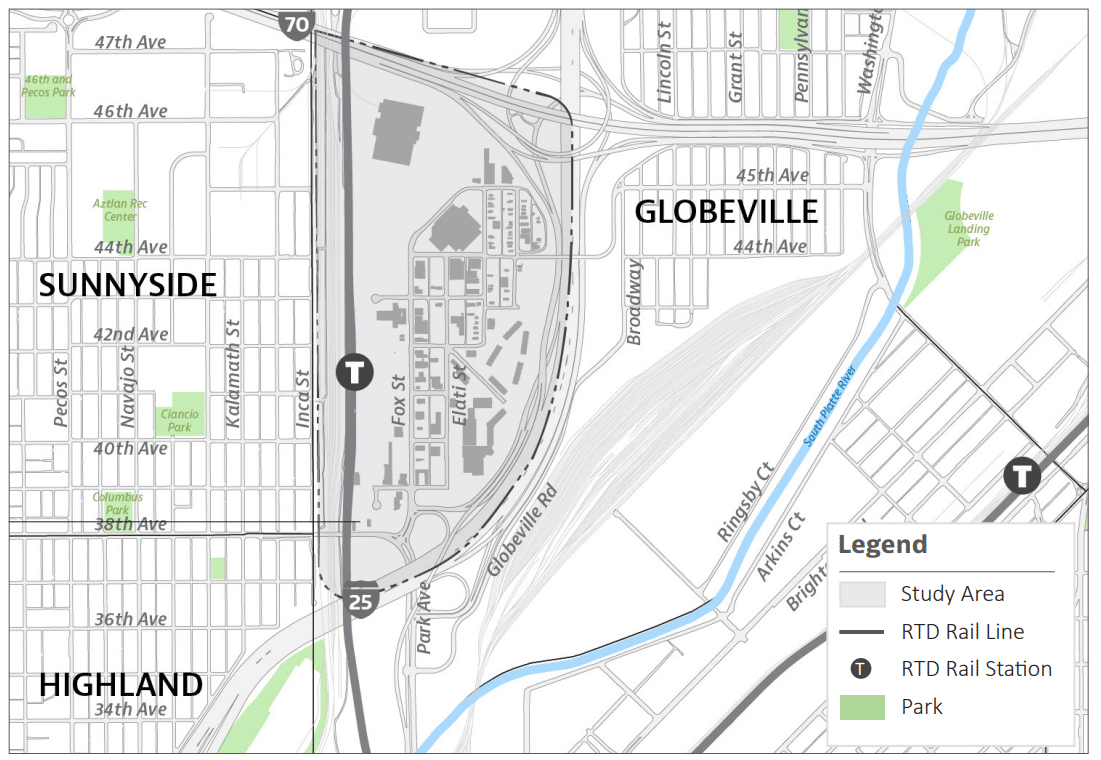

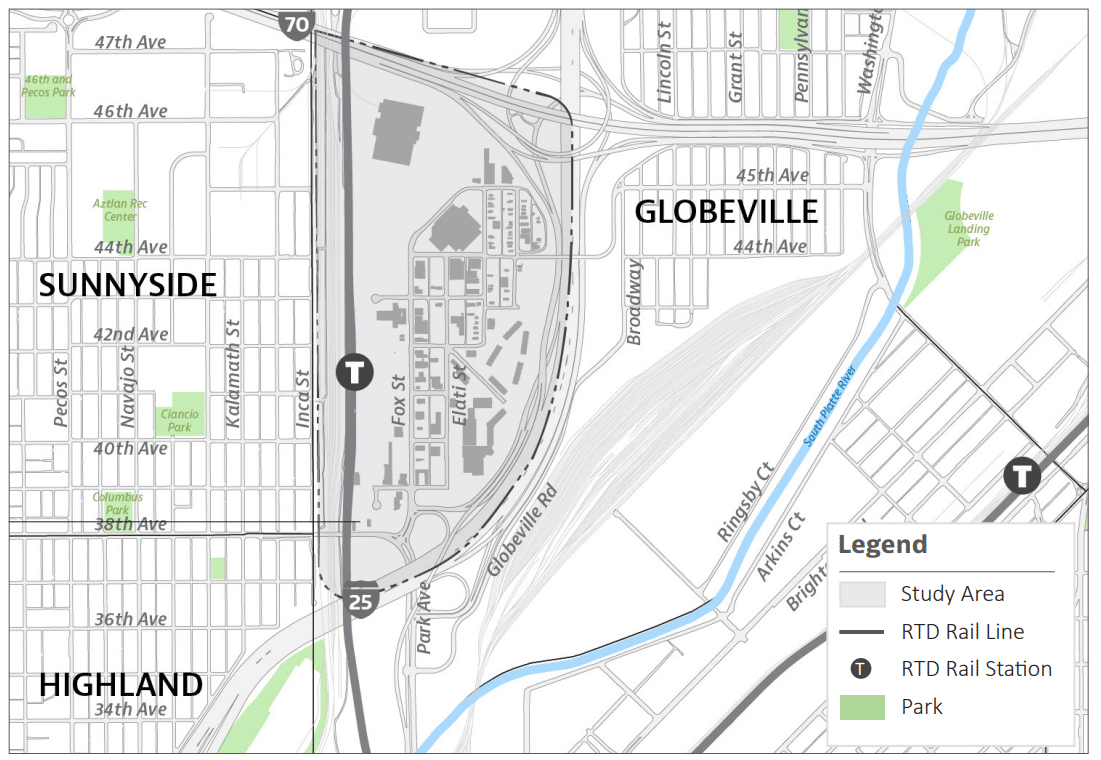

A map showing, in gray, the boundaries of Fox Island. (City of Denver)

Two roads in

There are two ways to drive into Fox Island.

One of the spots is what Nevitt calls the “cluster,” where Fox Street runs north from the junction of Park and 38th avenues. Some people turning here quickly jump on an on-ramp to I-25. But for those who stay on Fox, it slims down to two lanes, one in each direction.

The other entry point is 44th Avenue, where there’s a bridge over I-25 to the rest of Globeville. It is also two lanes, and “we’ve made a strong commitment to Globeville that it will remain a two-lane road,” Nevitt said.

Those not using a car have other ways to access Fox Island. There’s the RTD station, which is just one stop from downtown. A pedestrian bridge runs over the tracks, connecting it to neighboring Sunnyside. And there are sidewalks along the main streets.

The station is why the city sees the area eventually becoming “just about the densest TOD we have,” according to Nevitt, referring to transit-oriented development.

“There are places where we expect 20 stories here,” he said.

Some development is already underway in the neighborhood. A plan to top a Home Depot with two towers didn’t come to fruition. But Atlanta-based RangeWater Real Estate and Denver-based Highland Development Co. have separate apartment projects near completion, and Denver’s Central Street Capital broke ground on another one last month. More are planned.

“That kind of development is going to generate a lot of traffic,” Nevitt said.

The view of the “cluster” at the southern end of Fox Island, as seen looking south from the roof of Assembly Student Living. Fox Street runs north from 38th Avenue, which runs under Interstate 25. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

The trip cap

Given the limited access points, Nevitt said the city is wary of new development creating “catastrophic gridlock,” where emergency services can’t get into Fox Island. There is no police station within it. Nor is there a fire station.

So in 2018, after holding public meetings, the city put the rules in place.

A key part of that was trip capacity limits. The rules stated that, until new or improved vehicle infrastructure was in place — like another bridge out of the neighborhood — Fox Island would be limited to 25,000 trips.

Trips are somewhat hypothetical, but represent each time a vehicle crosses the neighborhood’s boundaries. A resident driving to the suburbs for work and arriving home eight hours later, for example, would be two trips. The idea grew from a cap on parking spots, which the city initially considered.

When the rules were passed, there were already buildings and businesses and homes on many properties in Fox Island. Those were awarded trips corresponding to the property use. The RTD station, which has a huge parking lot, was awarded 1,500 trips to account for those driving in to catch a train.

That left 12,995 trips available for what would be built. Since 2018, they’ve been tracked by a public online spreadsheet.

Denver has worked to get developers to think about other modes of transportation too. “We really put a lot of pressure on every development that came forward,” Nevitt said, to do things like provide residents with annual RTD passes or build an amazing bike storage room.

“And people have done that,” he said.

A two-lane bridge over Interstate 25 connects Fox Island with the rest of Denver’s Globeville neighborhood. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

Still, with the trip cap, the city “created a gold rush,” said Isiah Salazar, an executive with Central Street Capital.

CSC has been in the neighborhood since 2004, when it purchased the former Regency Hotel and turned it into the Assembly Student Living apartment complex. The family office and development firm now believes it is the area’s second-largest property owner.

CSC recently broke ground on a 224-unit apartment building at 4040 Fox St. The project required 854 trips, and was one of the last to be awarded any.

Salazar noted that while trips are “reserved” for a project early on, they are only actually awarded when the project’s site development plan, or SDP, is approved. How fast that approval comes depends in part on city staff, who have been dealing with a backlog of plans.

In the final months of review, with the number of available trips dwindling, Salazar said he was mildly paranoid that the company’s SDP wouldn’t be approved in time.

“We had a level of anxiety where some other property owner/developer might swing in and snag them,” he said.

A view of Fox Island, looking northwest from the roof of Assembly Student Living. The massive parking lot serves RTD’s 41st and Fox station. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

The ramifications

Gruber, the broker, said Fox Island no longer works well for industrial businesses. Property taxes have gone up, development is poised to bring more pedestrian traffic and access for semi-trucks is “obsolete,” although plenty still rumble through.

Denver’s light and commuter rail network is relatively new, meaning 41st and Fox isn’t the only station to come on line in recent years. In RiNo, development has boomed around the 38th and Blake station, which was also once largely industrial. There, many property owners have sold to developers, who in turn have built apartments or office space. Auto shops and manufacturers have left for spots further from downtown.

But that cycle is no longer happening in Fox Island, Gruber said, because an industrial property without trips is no use to a developer.

“No developers want to jump on a property that they can’t develop,” Gruber said. “It’s frustrating as a broker. I think it’s frustrating for owners as well.”

“The city is effectively capping the real estate there as industrial, but the buildings don’t work as industrial,” he said.

Savills broker Matt Emmons, who has also done deals in Fox Island, echoed that assessment. He recently had a full city block assemblage — multiple owners who were willing to sell to one buyer. That would normally allow a developer to build a huge project.

“With no trips, we weren’t able to generate any interest,” Emmons said.

John Streelman, an attorney with Nelson Mullins representing multiple Fox Island owners, sent Nevitt a letter last month raising “significant concerns about the damage and irreparable harm” caused by the trip cap.

Streelman’s letter posed 16 questions, including whether the city had any plans to compensate affected landowners and whether the city had considered “less intrusive or harmful means” to accomplish its goals.

While CSC is building apartments at 4040 Fox St., the firm also owns multiple undeveloped lots nearby. It would like to do something with them, but any building would require trips, and there aren’t more trips to be had.

“We’re basically hitting the brakes on what we can develop in the neighborhood,” Salazar said.

Tomorrow in BusinessDen: Denver’s plan to reduce or eliminate the trip capacity restriction in Fox Island hinges on private developers, most notably a joint venture working to bring new life to a long-vacant former Denver Post printing facility.

Downtown Denver looms in the background as a truck rumbles north in Fox Island, a 185-acre neighborhood surrounded by interstates and railroad tracks. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

Editor’s note: This is the first half of a two-part series. To read Part 2, click the link: “Island tripping: Denver’s plan to relieve restriction hinges on private developers”

They call it Fox Island.

It’s a 185-acre pocket of Denver, technically part of Globeville, surrounded not by water but by transportation corridors — Interstate 70 to the north, Interstate 25 to the east and south, and railroad tracks to the west.

Fox Street is the one main road that traverses it.

“It really is an island,” said Chris Nevitt, Denver’s manager for transit-oriented development. “The street grid does not penetrate it at all, except for two spots.”

In 2019, the neighborhood got an RTD rail station, known as 41st and Fox. That effectively ensured that the largely industrial neighborhood, which also has a smattering of older homes, would become a hot spot for redevelopment, particularly new housing.

And that is indeed happening — to the extent that the City of Denver allows it.

If you own a property in Fox Island today, it’s unlikely you can get a developer to buy it.

Russell Gruber, a commercial real estate broker, has been marketing industrial properties in the neighborhood for 16 years. He estimates he knows 85 percent of the owners.

But the head of Gruber Commercial Real Estate said he’s now turning down business there.

“I’m literally passing on listings in this neighborhood,” he said. “Because there’s been nothing I can do for them. I’ll just put up a sign.”

It’s a result of an only-in-Fox-Island restriction: the trip cap.

City rules implemented in 2018 mean developers can build something in Fox Island only if they are allotted a certain number of “trips.” The number is meant to correspond to how much additional vehicle traffic their project will add to the area.

No other part of Denver has a similar restriction. And, from the start, because of the limited access points, the number of trips that could be claimed was capped. So while the rules have been in place for five years, a key thing happened in 2023 in Fox Island, which still has a host of undeveloped and underutilized lots.

“We have used up all the available trips,” Nevitt said.

A map showing, in gray, the boundaries of Fox Island. (City of Denver)

Two roads in

There are two ways to drive into Fox Island.

One of the spots is what Nevitt calls the “cluster,” where Fox Street runs north from the junction of Park and 38th avenues. Some people turning here quickly jump on an on-ramp to I-25. But for those who stay on Fox, it slims down to two lanes, one in each direction.

The other entry point is 44th Avenue, where there’s a bridge over I-25 to the rest of Globeville. It is also two lanes, and “we’ve made a strong commitment to Globeville that it will remain a two-lane road,” Nevitt said.

Those not using a car have other ways to access Fox Island. There’s the RTD station, which is just one stop from downtown. A pedestrian bridge runs over the tracks, connecting it to neighboring Sunnyside. And there are sidewalks along the main streets.

The station is why the city sees the area eventually becoming “just about the densest TOD we have,” according to Nevitt, referring to transit-oriented development.

“There are places where we expect 20 stories here,” he said.

Some development is already underway in the neighborhood. A plan to top a Home Depot with two towers didn’t come to fruition. But Atlanta-based RangeWater Real Estate and Denver-based Highland Development Co. have separate apartment projects near completion, and Denver’s Central Street Capital broke ground on another one last month. More are planned.

“That kind of development is going to generate a lot of traffic,” Nevitt said.

The view of the “cluster” at the southern end of Fox Island, as seen looking south from the roof of Assembly Student Living. Fox Street runs north from 38th Avenue, which runs under Interstate 25. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

The trip cap

Given the limited access points, Nevitt said the city is wary of new development creating “catastrophic gridlock,” where emergency services can’t get into Fox Island. There is no police station within it. Nor is there a fire station.

So in 2018, after holding public meetings, the city put the rules in place.

A key part of that was trip capacity limits. The rules stated that, until new or improved vehicle infrastructure was in place — like another bridge out of the neighborhood — Fox Island would be limited to 25,000 trips.

Trips are somewhat hypothetical, but represent each time a vehicle crosses the neighborhood’s boundaries. A resident driving to the suburbs for work and arriving home eight hours later, for example, would be two trips. The idea grew from a cap on parking spots, which the city initially considered.

When the rules were passed, there were already buildings and businesses and homes on many properties in Fox Island. Those were awarded trips corresponding to the property use. The RTD station, which has a huge parking lot, was awarded 1,500 trips to account for those driving in to catch a train.

That left 12,995 trips available for what would be built. Since 2018, they’ve been tracked by a public online spreadsheet.

Denver has worked to get developers to think about other modes of transportation too. “We really put a lot of pressure on every development that came forward,” Nevitt said, to do things like provide residents with annual RTD passes or build an amazing bike storage room.

“And people have done that,” he said.

A two-lane bridge over Interstate 25 connects Fox Island with the rest of Denver’s Globeville neighborhood. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

Still, with the trip cap, the city “created a gold rush,” said Isiah Salazar, an executive with Central Street Capital.

CSC has been in the neighborhood since 2004, when it purchased the former Regency Hotel and turned it into the Assembly Student Living apartment complex. The family office and development firm now believes it is the area’s second-largest property owner.

CSC recently broke ground on a 224-unit apartment building at 4040 Fox St. The project required 854 trips, and was one of the last to be awarded any.

Salazar noted that while trips are “reserved” for a project early on, they are only actually awarded when the project’s site development plan, or SDP, is approved. How fast that approval comes depends in part on city staff, who have been dealing with a backlog of plans.

In the final months of review, with the number of available trips dwindling, Salazar said he was mildly paranoid that the company’s SDP wouldn’t be approved in time.

“We had a level of anxiety where some other property owner/developer might swing in and snag them,” he said.

A view of Fox Island, looking northwest from the roof of Assembly Student Living. The massive parking lot serves RTD’s 41st and Fox station. (Thomas Gounley/BusinessDen)

The ramifications

Gruber, the broker, said Fox Island no longer works well for industrial businesses. Property taxes have gone up, development is poised to bring more pedestrian traffic and access for semi-trucks is “obsolete,” although plenty still rumble through.

Denver’s light and commuter rail network is relatively new, meaning 41st and Fox isn’t the only station to come on line in recent years. In RiNo, development has boomed around the 38th and Blake station, which was also once largely industrial. There, many property owners have sold to developers, who in turn have built apartments or office space. Auto shops and manufacturers have left for spots further from downtown.

But that cycle is no longer happening in Fox Island, Gruber said, because an industrial property without trips is no use to a developer.

“No developers want to jump on a property that they can’t develop,” Gruber said. “It’s frustrating as a broker. I think it’s frustrating for owners as well.”

“The city is effectively capping the real estate there as industrial, but the buildings don’t work as industrial,” he said.

Savills broker Matt Emmons, who has also done deals in Fox Island, echoed that assessment. He recently had a full city block assemblage — multiple owners who were willing to sell to one buyer. That would normally allow a developer to build a huge project.

“With no trips, we weren’t able to generate any interest,” Emmons said.

John Streelman, an attorney with Nelson Mullins representing multiple Fox Island owners, sent Nevitt a letter last month raising “significant concerns about the damage and irreparable harm” caused by the trip cap.

Streelman’s letter posed 16 questions, including whether the city had any plans to compensate affected landowners and whether the city had considered “less intrusive or harmful means” to accomplish its goals.

While CSC is building apartments at 4040 Fox St., the firm also owns multiple undeveloped lots nearby. It would like to do something with them, but any building would require trips, and there aren’t more trips to be had.

“We’re basically hitting the brakes on what we can develop in the neighborhood,” Salazar said.

Tomorrow in BusinessDen: Denver’s plan to reduce or eliminate the trip capacity restriction in Fox Island hinges on private developers, most notably a joint venture working to bring new life to a long-vacant former Denver Post printing facility.