Rabbi David Araiev, 33, poses for a portrait on East Mississippi Avenue near the Ohr Avner synagogue in Aurora on Tuesday. The eruv was installed in the city six years ago. (Grace Smith/The Denver Post)

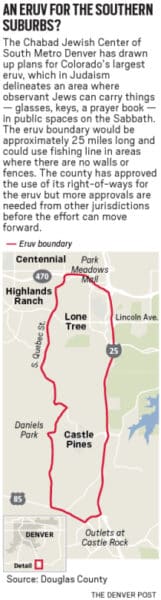

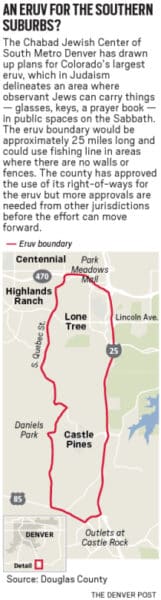

In an area stretching from Lone Tree to Castle Pines — using fence, wall and fishing line — the Chabad Jewish Center of South Metro Denver is exploring plans to erect Colorado’s largest eruv.

An eruv delineates an area where observant, often Orthodox, Jews are permitted to carry things on the Sabbath — from a prayer book to keys to reading glasses — that religious dictates otherwise forbid. More practically, it allows the faithful to leave the confines of home on a holy day to venture into public spaces without violating rabbinical tenets, be it a mother pushing a baby stroller to the park or someone picking up medicine at the pharmacy.

Eruvs typically follow existing infrastructure, like fences and walls, but where that isn’t present a monofilament line is strung up between lampposts and telephone poles to serve as a boundary.

“It allows the elderly and young families to be out and about and be a part of the community,” Shmuel Halpern, rabbi at the Young Israel of Denver synagogue in east Denver, said of an eruv. “It’s crucial for young families and for those who are infirm — or they would be completely homebound.”

East Denver has had an eruv for years and even maintains an online status page indicating any breaks or needed repairs. There are also eruvs in Greenwood Village and Aurora. But none come close to the size of the one being pitched in Douglas County, the boundary of which would run approximately 25 miles in length, according to maps submitted by the Chabad Jewish Center of South Metro Denver.

Avraham Mintz, rabbi at the center in Lone Tree, declined to speak to The Denver Post about the project. But the Douglas County commissioners approved a licensing agreement with the center this spring that allows “the eruv monofilament line (200-pound test fishing line) to be installed within the public right-of-way.”

Avraham Mintz, rabbi at the center in Lone Tree, declined to speak to The Denver Post about the project. But the Douglas County commissioners approved a licensing agreement with the center this spring that allows “the eruv monofilament line (200-pound test fishing line) to be installed within the public right-of-way.”

The county said Xcel Energy has already signed off on the use of its street light poles for the eruv. A spokesperson for Castle Pines said the city is aware of the proposal but has not yet received an application from Chabad Jewish Center.

Matt Williams, assistant director of public works and engineering for Douglas County, said the county’s big concern is to make sure that any line that is installed has plenty of clearance for the largest vehicles on the road.

“They came in with 20 feet high and that was more than enough,” he said.

Williams said the use of a fishing line as a boundary would occur mostly along Quebec Street and Monarch Boulevard in Highlands Ranch, from C-470 to Rock Canyon High School. The eruv’s eastern edge appears to follow the Interstate 25 corridor, with perhaps a highway sound wall or wildlife fencing serving as a boundary.

The county, Williams said, frequently deals with requests to use its right of ways but never at this scale.

“It was just the sheer size of the request that was unusual,” he said of the eruv.

But Douglas County’s eruv wouldn’t be the nation’s largest. That honor likely goes to the Los Angeles Community Eruv, or L.A. Eruv, which covers 100 to 110 square miles of the nation’s second-largest city and is bounded by giant highways like the Ventura, Santa Monica and San Diego freeways, according to Executive Director Howard Witkin.

“The vast majority of our eruv are solid walls — sound walls and fences along the freeways and the L.A. River,” Witkin said. “Where we cross streets and other breaks in the eruv, we use 200-pound fishing line to build ‘doorways.’”

The biggest challenge, he said, is “finding the manpower to inspect and repair a larger perimeter.”

“We have three rabbinical experts that inspect the full eruv every week, and we have a four-man crew and our own lift truck that do repairs every week,” Witkin said. “We have repairs every week but since we went live, we have been up 1,550 weeks and down twice.”

The eruv, which encompasses about 50,000 observant Jews, had to get permits from multiple municipalities and utilities before it could be established, including Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, CalTrans, the Federal Highway Department, fire departments and the L.A. Bureau of Street Lighting.

“There are 39 categories of creative effort through which humans improve and lift the world — building, commerce, farming, sewing, writing et al, including logistics and shipping,” Witkin said. “On the Sabbath, we refrain from making those changes to our world.”

He compared an eruv to “the original neighborhood association” that “serves to clearly mark the extent of the community, its boundaries and its residents.”

Williams said the use of a fishing line as a boundary would occur mostly along Quebec Street and Monarch Boulevard in Highlands Ranch, from C-470 to Rock Canyon High School. The eruv’s eastern edge appears to follow the Interstate 25 corridor, with perhaps a highway sound wall or wildlife fencing serving as a boundary.

The county, Williams said, frequently deals with requests to use its right of ways but never at this scale.

“It was just the sheer size of the request that was unusual,” he said of the eruv.

“The vast majority of our eruv are solid walls — sound walls and fences along the freeways and the L.A. River,” Witkin said. “Where we cross streets and other breaks in the eruv, we use 200-pound fishing line to build ‘doorways.’”

The biggest challenge, he said, is “finding the manpower to inspect and repair a larger perimeter.”

“We have three rabbinical experts that inspect the full eruv every week, and we have a four-man crew and our own lift truck that do repairs every week,” Witkin said. “We have repairs every week but since we went live, we have been up 1,550 weeks and down twice.”

The eruv, which encompasses about 50,000 observant Jews, had to get permits from multiple municipalities and utilities before it could be established, including Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, CalTrans, the Federal Highway Department, fire departments and the L.A. Bureau of Street Lighting.

“There are 39 categories of creative effort through which humans improve and lift the world — building, commerce, farming, sewing, writing et. al., including logistics and shipping,” Witkin said. “On the Sabbath, we refrain from making those changes to our world.”

He compared an eruv to “the original neighborhood association” that “serves to clearly mark the extent of the community, its boundaries and its residents.”

This story was originally published by The Denver Post, a BusinessDen news partner.

Rabbi David Araiev, 33, poses for a portrait on East Mississippi Avenue near the Ohr Avner synagogue in Aurora on Tuesday. The eruv was installed in the city six years ago. (Grace Smith/The Denver Post)

In an area stretching from Lone Tree to Castle Pines — using fence, wall and fishing line — the Chabad Jewish Center of South Metro Denver is exploring plans to erect Colorado’s largest eruv.

An eruv delineates an area where observant, often Orthodox, Jews are permitted to carry things on the Sabbath — from a prayer book to keys to reading glasses — that religious dictates otherwise forbid. More practically, it allows the faithful to leave the confines of home on a holy day to venture into public spaces without violating rabbinical tenets, be it a mother pushing a baby stroller to the park or someone picking up medicine at the pharmacy.

Eruvs typically follow existing infrastructure, like fences and walls, but where that isn’t present a monofilament line is strung up between lampposts and telephone poles to serve as a boundary.

“It allows the elderly and young families to be out and about and be a part of the community,” Shmuel Halpern, rabbi at the Young Israel of Denver synagogue in east Denver, said of an eruv. “It’s crucial for young families and for those who are infirm — or they would be completely homebound.”

East Denver has had an eruv for years and even maintains an online status page indicating any breaks or needed repairs. There are also eruvs in Greenwood Village and Aurora. But none come close to the size of the one being pitched in Douglas County, the boundary of which would run approximately 25 miles in length, according to maps submitted by the Chabad Jewish Center of South Metro Denver.

Avraham Mintz, rabbi at the center in Lone Tree, declined to speak to The Denver Post about the project. But the Douglas County commissioners approved a licensing agreement with the center this spring that allows “the eruv monofilament line (200-pound test fishing line) to be installed within the public right-of-way.”

Avraham Mintz, rabbi at the center in Lone Tree, declined to speak to The Denver Post about the project. But the Douglas County commissioners approved a licensing agreement with the center this spring that allows “the eruv monofilament line (200-pound test fishing line) to be installed within the public right-of-way.”

The county said Xcel Energy has already signed off on the use of its street light poles for the eruv. A spokesperson for Castle Pines said the city is aware of the proposal but has not yet received an application from Chabad Jewish Center.

Matt Williams, assistant director of public works and engineering for Douglas County, said the county’s big concern is to make sure that any line that is installed has plenty of clearance for the largest vehicles on the road.

“They came in with 20 feet high and that was more than enough,” he said.

Williams said the use of a fishing line as a boundary would occur mostly along Quebec Street and Monarch Boulevard in Highlands Ranch, from C-470 to Rock Canyon High School. The eruv’s eastern edge appears to follow the Interstate 25 corridor, with perhaps a highway sound wall or wildlife fencing serving as a boundary.

The county, Williams said, frequently deals with requests to use its right of ways but never at this scale.

“It was just the sheer size of the request that was unusual,” he said of the eruv.

But Douglas County’s eruv wouldn’t be the nation’s largest. That honor likely goes to the Los Angeles Community Eruv, or L.A. Eruv, which covers 100 to 110 square miles of the nation’s second-largest city and is bounded by giant highways like the Ventura, Santa Monica and San Diego freeways, according to Executive Director Howard Witkin.

“The vast majority of our eruv are solid walls — sound walls and fences along the freeways and the L.A. River,” Witkin said. “Where we cross streets and other breaks in the eruv, we use 200-pound fishing line to build ‘doorways.’”

The biggest challenge, he said, is “finding the manpower to inspect and repair a larger perimeter.”

“We have three rabbinical experts that inspect the full eruv every week, and we have a four-man crew and our own lift truck that do repairs every week,” Witkin said. “We have repairs every week but since we went live, we have been up 1,550 weeks and down twice.”

The eruv, which encompasses about 50,000 observant Jews, had to get permits from multiple municipalities and utilities before it could be established, including Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, CalTrans, the Federal Highway Department, fire departments and the L.A. Bureau of Street Lighting.

“There are 39 categories of creative effort through which humans improve and lift the world — building, commerce, farming, sewing, writing et al, including logistics and shipping,” Witkin said. “On the Sabbath, we refrain from making those changes to our world.”

He compared an eruv to “the original neighborhood association” that “serves to clearly mark the extent of the community, its boundaries and its residents.”

Williams said the use of a fishing line as a boundary would occur mostly along Quebec Street and Monarch Boulevard in Highlands Ranch, from C-470 to Rock Canyon High School. The eruv’s eastern edge appears to follow the Interstate 25 corridor, with perhaps a highway sound wall or wildlife fencing serving as a boundary.

The county, Williams said, frequently deals with requests to use its right of ways but never at this scale.

“It was just the sheer size of the request that was unusual,” he said of the eruv.

“The vast majority of our eruv are solid walls — sound walls and fences along the freeways and the L.A. River,” Witkin said. “Where we cross streets and other breaks in the eruv, we use 200-pound fishing line to build ‘doorways.’”

The biggest challenge, he said, is “finding the manpower to inspect and repair a larger perimeter.”

“We have three rabbinical experts that inspect the full eruv every week, and we have a four-man crew and our own lift truck that do repairs every week,” Witkin said. “We have repairs every week but since we went live, we have been up 1,550 weeks and down twice.”

The eruv, which encompasses about 50,000 observant Jews, had to get permits from multiple municipalities and utilities before it could be established, including Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, CalTrans, the Federal Highway Department, fire departments and the L.A. Bureau of Street Lighting.

“There are 39 categories of creative effort through which humans improve and lift the world — building, commerce, farming, sewing, writing et. al., including logistics and shipping,” Witkin said. “On the Sabbath, we refrain from making those changes to our world.”

He compared an eruv to “the original neighborhood association” that “serves to clearly mark the extent of the community, its boundaries and its residents.”

This story was originally published by The Denver Post, a BusinessDen news partner.