Cole Chandler, founder of Colorado Village Collaborative, in front of the nonprofit’s homeless campsite Dec. 16 at the Denver Human Services east branch in Clayton. (BusinessDen file photo)

Cole Chandler runs an organization that provides support to the homeless.

But it doesn’t always feel that way.

“Right now, some days it feels like we’re running a moving company,” he said.

The nonprofit that Chandler founded, Colorado Village Collaborative, operates two types of temporary housing in Denver. There are tiny home villages, in which individuals that would be homeless stay in small structures. The first opened in 2017. And there are sanctioned encampments, in which individuals live in ice-fishing tents set up on a fenced parking lot, one step up from the streets. The first of those opened in late 2020.

Both of the operations are approved by Denver on a temporary basis, meaning they must relocate after a period that generally ranges from six months to a couple years. Chandler strikes short-term lease arrangements with the landowners, which have included the city, various churches, Regis University and Denver Health. The facilities have a staff member on site 24/7.

The arrangement has worked well so far, according to Chandler, who says the organization has served more than 400 people and seen 120 graduate into longer-term housing. But the temporary nature of CVC’s installations has also become a “bottleneck to our growth,” he said.

“This year alone, we’re relocating four sites,” he said. “And next year we’re scheduled to relocate three more.”

And that’s why, as CVC hits five years since its 2017 launch, Chandler wants the organization — whose 2022 budget is $5.2 million — to own its own property.

He said the organization would like to buy either an acre or two of vacant land, or an old motel with a sizable parking lot. He’s open to anywhere in the city.

Chandler said he’s inspired in part by a full city block in Cole, where CVC currently has one of its tiny home villages set up. While undeveloped now, Mile High Ministries plans to build 65 income-restricted apartments on a portion of the site, and Habitat for Humanity has 17 for-sale townhomes in the works. A commercial building will round out the project.

“My vision would be that ultimately CVC would be able to develop a project like that,” he said.

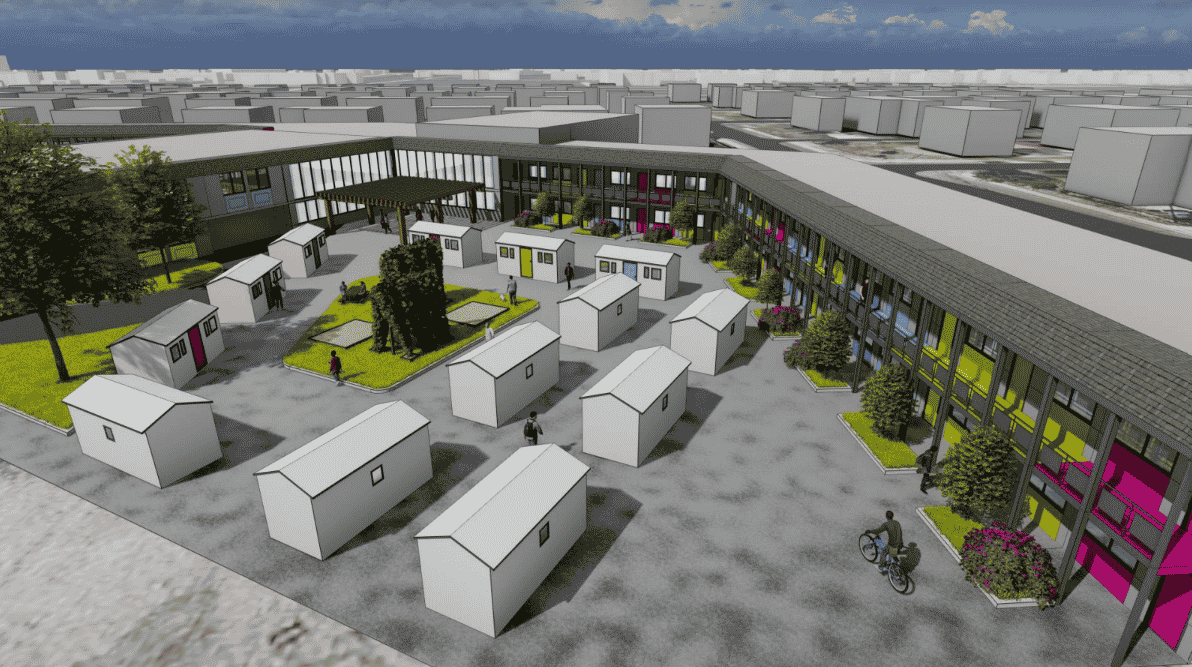

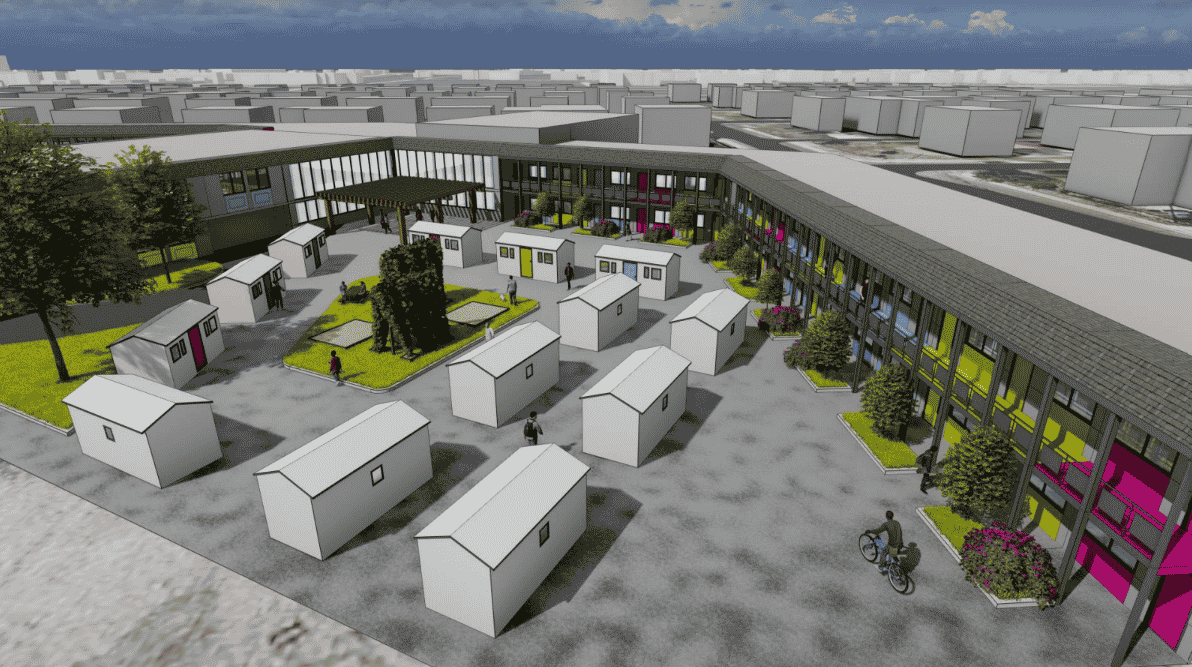

A rendering of a hypothetical Colorado Village Collaborative motel-based campus. (Image courtesy of Colorado Village Collaborative)

Chandler does envision a slight twist on the model. He wants a project that will incorporate long-term affordable housing (“a piece of the permanent solution”) with the two communities CVC is known for: a campsite or a tiny home village, offering an “entry point” from the streets. Finally, he wants some sort of space that would provide services to residents, such as mental health counseling.

While he’s open to vacant land, Chandler said he sees an old motel as a more immediate path to his vision. The old motel rooms would be converted into single-room occupancy units. The ice fishing tents or tiny homes could be on the parking lot. And the former motel office could be used to offer services.

Chandler said CVC figures it is willing to spend about $20 million to buy a motel, fix it up and operate it for one year. That means the acquisition itself would likely need to come in under the $10 million mark.

CVC has launched a “Five Years Young” fundraising campaign for the potential acquisition and other future expenses.

CVC isn’t the first homeless-minded organization eyeing old motels. Denver has spent tens of millions of dollars since the pandemic began to lease entire motels. The rooms are used to house homeless individuals seen as vulnerable. Some downtown residents recently pushed back on the renewal of one such contract.

The city also said last year it wants to use federal funds to buy a former Stay Inn in northeast Denver. And Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, a Denver-based nonprofit, also purchased a motel in late 2019 and turned it into apartments.

Chandler said he still thinks that CVC’s vision is unique. “We’re proposing not only the hotel model but also the activated parking lot,” he said.

“Our mission is to bridge the gaps between the streets and stable housing,” he said.

Chandler also said that most interest in motels, like that coming from the city, has been for “non-congregate shelter” for emergency use, whereas CVC’s use would be more comparable to an apartment building.

Chandler said that, if CVC does end up buying property, the organization will likely continue operating temporary camps and villages. But he doesn’t think they should be the only thing CVC does.

“We aren’t out here to be innovative for the sake of being innovative,” he said. “There are proven models out there.”

Cole Chandler, founder of Colorado Village Collaborative, in front of the nonprofit’s homeless campsite Dec. 16 at the Denver Human Services east branch in Clayton. (BusinessDen file photo)

Cole Chandler runs an organization that provides support to the homeless.

But it doesn’t always feel that way.

“Right now, some days it feels like we’re running a moving company,” he said.

The nonprofit that Chandler founded, Colorado Village Collaborative, operates two types of temporary housing in Denver. There are tiny home villages, in which individuals that would be homeless stay in small structures. The first opened in 2017. And there are sanctioned encampments, in which individuals live in ice-fishing tents set up on a fenced parking lot, one step up from the streets. The first of those opened in late 2020.

Both of the operations are approved by Denver on a temporary basis, meaning they must relocate after a period that generally ranges from six months to a couple years. Chandler strikes short-term lease arrangements with the landowners, which have included the city, various churches, Regis University and Denver Health. The facilities have a staff member on site 24/7.

The arrangement has worked well so far, according to Chandler, who says the organization has served more than 400 people and seen 120 graduate into longer-term housing. But the temporary nature of CVC’s installations has also become a “bottleneck to our growth,” he said.

“This year alone, we’re relocating four sites,” he said. “And next year we’re scheduled to relocate three more.”

And that’s why, as CVC hits five years since its 2017 launch, Chandler wants the organization — whose 2022 budget is $5.2 million — to own its own property.

He said the organization would like to buy either an acre or two of vacant land, or an old motel with a sizable parking lot. He’s open to anywhere in the city.

Chandler said he’s inspired in part by a full city block in Cole, where CVC currently has one of its tiny home villages set up. While undeveloped now, Mile High Ministries plans to build 65 income-restricted apartments on a portion of the site, and Habitat for Humanity has 17 for-sale townhomes in the works. A commercial building will round out the project.

“My vision would be that ultimately CVC would be able to develop a project like that,” he said.

A rendering of a hypothetical Colorado Village Collaborative motel-based campus. (Image courtesy of Colorado Village Collaborative)

Chandler does envision a slight twist on the model. He wants a project that will incorporate long-term affordable housing (“a piece of the permanent solution”) with the two communities CVC is known for: a campsite or a tiny home village, offering an “entry point” from the streets. Finally, he wants some sort of space that would provide services to residents, such as mental health counseling.

While he’s open to vacant land, Chandler said he sees an old motel as a more immediate path to his vision. The old motel rooms would be converted into single-room occupancy units. The ice fishing tents or tiny homes could be on the parking lot. And the former motel office could be used to offer services.

Chandler said CVC figures it is willing to spend about $20 million to buy a motel, fix it up and operate it for one year. That means the acquisition itself would likely need to come in under the $10 million mark.

CVC has launched a “Five Years Young” fundraising campaign for the potential acquisition and other future expenses.

CVC isn’t the first homeless-minded organization eyeing old motels. Denver has spent tens of millions of dollars since the pandemic began to lease entire motels. The rooms are used to house homeless individuals seen as vulnerable. Some downtown residents recently pushed back on the renewal of one such contract.

The city also said last year it wants to use federal funds to buy a former Stay Inn in northeast Denver. And Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, a Denver-based nonprofit, also purchased a motel in late 2019 and turned it into apartments.

Chandler said he still thinks that CVC’s vision is unique. “We’re proposing not only the hotel model but also the activated parking lot,” he said.

“Our mission is to bridge the gaps between the streets and stable housing,” he said.

Chandler also said that most interest in motels, like that coming from the city, has been for “non-congregate shelter” for emergency use, whereas CVC’s use would be more comparable to an apartment building.

Chandler said that, if CVC does end up buying property, the organization will likely continue operating temporary camps and villages. But he doesn’t think they should be the only thing CVC does.

“We aren’t out here to be innovative for the sake of being innovative,” he said. “There are proven models out there.”