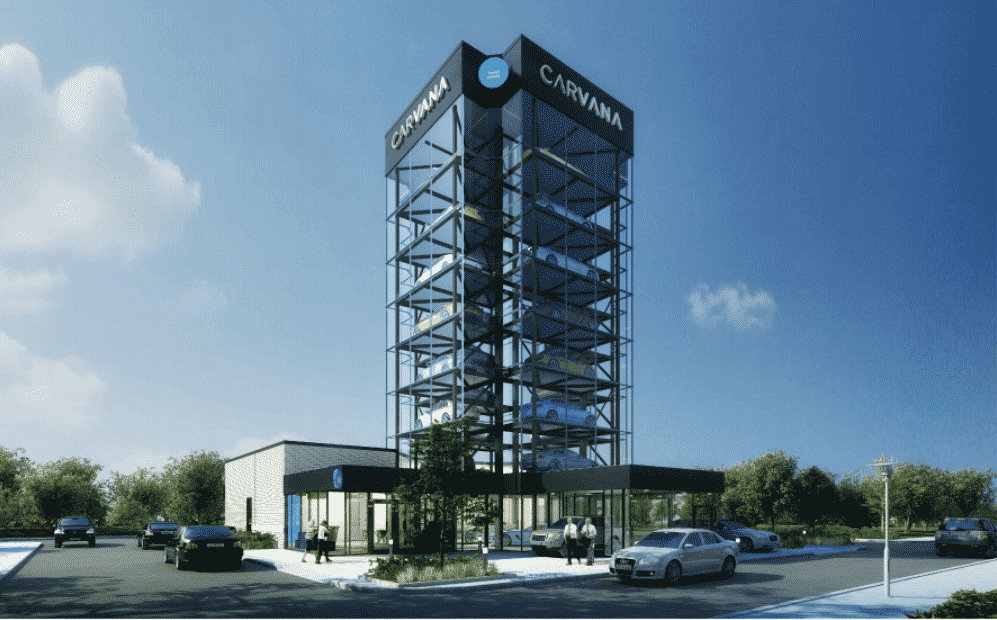

A rendering of the proposed building and “car vending machine” that online car seller Carvana wants to build at the I-25/Evans Avenue interchange. (Courtesy of public records)

It would be a glass structure, with eight levels of parked vehicles, to be rotated up and down as needed.

It would be 70 feet tall, and about 40 feet wide.

There’s a photo of what it would look like at the top of this page.

But beyond that, what truly is the nature of the structure that Arizona-based online car seller Carvana wants to build at the I-25/Evans Avenue interchange? That was the subject of a Denver Planning Board conversation earlier this month that seemed to veer into the philosophical.

“What we are approving, it’s different than what it’s presented to be,” board member Frank Schultz said at one point. “I just want to go on the record and say that.”

The Planning Board is the first body within the city that considers requests to rezone properties. It makes recommendations to the Denver City Council, which makes the final call on whether to approve or reject the requests.

The board isn’t supposed to consider the merits of a particular project that might be built on land if it is rezoned. Rather, it is legally required to merely consider whether it is appropriate for the land to have the new zoning, judging it on five criteria.

On Jan. 6, the board considered a request to rezone 4700 E. Evans Ave. from I-MX-3 — which allows a mix of uses up to three stories — to S-MX-8A, which stands for suburban mixed-use, with a max height of eight stories. The request was made by Carvana, which is looking to buy the currently undeveloped site from Denver-based Focus Properties.

BusinessDen reported in August on what Carvana wants to build at the site. At the meeting earlier this month, among the first to describe the proposed structure was Bret Sassenberg, Carvana’s senior director of real estate and development.

“The project that we plan to put at this location is one of our car vending machine towers,” he told the board.

Sassenberg went on to call the structure “a functioning automated parking system.” Customers that purchase a car online through Carvana can, in many markets including Denver, opt to have the vehicle delivered to their home. Alternatively, they can travel to what the company wants to build at I-25 and Evans, which Carvana has built in 24 cities around the country.

“We did make it exciting, and they drop a coin, because it was dubbed a car vending machine many years ago when we started in Atlanta,” Sassenberg said. “And their car will be brought down to ground level. And from there they drive off.”

But board member Frank Schultz, CEO of Tavern Hospitality Group, indicated that he considered the building to essentially be little more than a giant advertisement, one designed to attract the attention of the thousands of commuters passing by on the highway.

“We’re approving a billboard,” Schultz said. “That’s what’s happening.”

But Joel Noble, the chair of the board, said it shouldn’t be considered a billboard because the structure would be drawing attention to something actually physically present at the property.

“The zoning code refers to billboard as outdoor off-site advertising,” he said. “So you’re advertising something that isn’t here, it’s over there. The sign that says, come see a play, go drink Coke — whatever it is, it’s not on site.”

Noble, a software engineer and past president of a Curtis Park neighborhood organization, essentially compared Carvana’s proposed project to a department store window display.

“This concept that they might pursue under this zone district would be a multi-story shopfront, in some sense,” he said. “Like when you’re passing by a shopfront and they’ve got glass windows, you can see what’s in there, and you can decide if it’s attractive to me, etc. In this case, it’s multiple stories of that in their concept.”

But wary of getting too far off topic, Noble reiterated that Carvana’s project was “not relevant” to whether or not it was appropriate to rezone the property.

Board member Don Elliot, a director with a land-use consulting firm, made a recommendation for how members could say focused.

“I’ve listened to this conversation, guys, but for me, it gets much, much easier if you forget Carvana,” he said. “You never saw Carvana, you never heard the word Carvana.”

Schultz, meanwhile, maintained that whether or not a property can have a billboard is contingent on that zoning, and thus it would be relevant if Carvana’s planned structure were to be considered a billboard.

Schultz said he has actually been to a Carvana tower. The closest to Denver are in Kansas City and Tempe, Arizona.

“This is a novelty,” he said. “They did this in other states to get around that. They have to make it functional … I’ve been on your board for six years. I have a right to ask the question about what this is going to be. Because to me, I’m going to argue it’s a billboard, and is that an allowable use.”

Subsequently, in what would be the final stab at defining Carvana’s planned project, Noble called it “a novel way to display your products in a very visible way.”

Then he called for a vote, which despite the earlier back-and-forth resulted in unanimity. Eight votes to recommend approval, and none against.

Carvana’s rezoning request now moves on to the Denver City Council, where it would ultimately need to be approved by a majority. It is set to be considered by the council’s Land Use, Transportation and Infrastructure Committee on Tuesday.

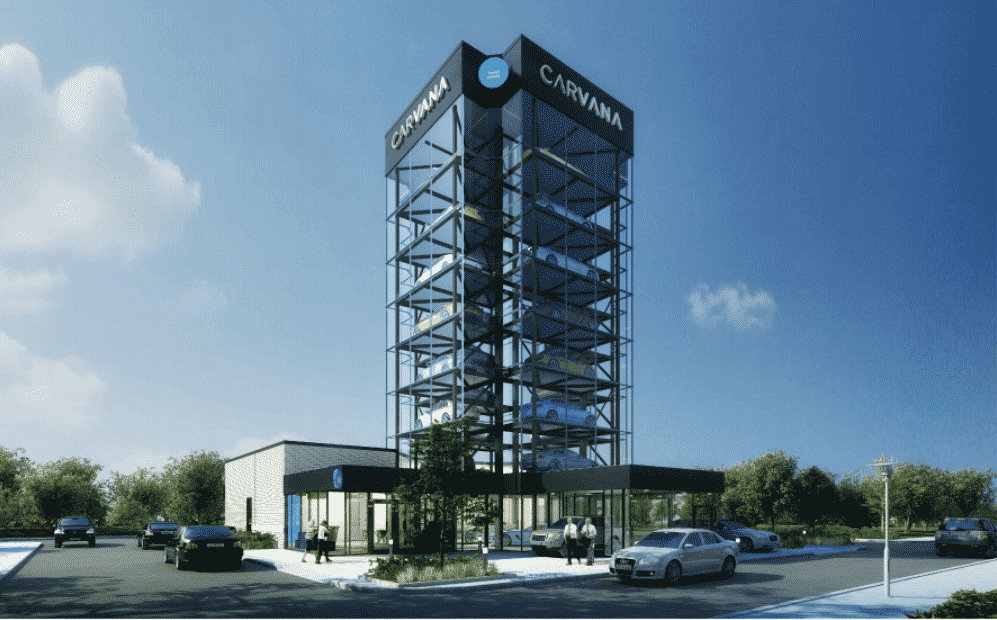

A rendering of the proposed building and “car vending machine” that online car seller Carvana wants to build at the I-25/Evans Avenue interchange. (Courtesy of public records)

It would be a glass structure, with eight levels of parked vehicles, to be rotated up and down as needed.

It would be 70 feet tall, and about 40 feet wide.

There’s a photo of what it would look like at the top of this page.

But beyond that, what truly is the nature of the structure that Arizona-based online car seller Carvana wants to build at the I-25/Evans Avenue interchange? That was the subject of a Denver Planning Board conversation earlier this month that seemed to veer into the philosophical.

“What we are approving, it’s different than what it’s presented to be,” board member Frank Schultz said at one point. “I just want to go on the record and say that.”

The Planning Board is the first body within the city that considers requests to rezone properties. It makes recommendations to the Denver City Council, which makes the final call on whether to approve or reject the requests.

The board isn’t supposed to consider the merits of a particular project that might be built on land if it is rezoned. Rather, it is legally required to merely consider whether it is appropriate for the land to have the new zoning, judging it on five criteria.

On Jan. 6, the board considered a request to rezone 4700 E. Evans Ave. from I-MX-3 — which allows a mix of uses up to three stories — to S-MX-8A, which stands for suburban mixed-use, with a max height of eight stories. The request was made by Carvana, which is looking to buy the currently undeveloped site from Denver-based Focus Properties.

BusinessDen reported in August on what Carvana wants to build at the site. At the meeting earlier this month, among the first to describe the proposed structure was Bret Sassenberg, Carvana’s senior director of real estate and development.

“The project that we plan to put at this location is one of our car vending machine towers,” he told the board.

Sassenberg went on to call the structure “a functioning automated parking system.” Customers that purchase a car online through Carvana can, in many markets including Denver, opt to have the vehicle delivered to their home. Alternatively, they can travel to what the company wants to build at I-25 and Evans, which Carvana has built in 24 cities around the country.

“We did make it exciting, and they drop a coin, because it was dubbed a car vending machine many years ago when we started in Atlanta,” Sassenberg said. “And their car will be brought down to ground level. And from there they drive off.”

But board member Frank Schultz, CEO of Tavern Hospitality Group, indicated that he considered the building to essentially be little more than a giant advertisement, one designed to attract the attention of the thousands of commuters passing by on the highway.

“We’re approving a billboard,” Schultz said. “That’s what’s happening.”

But Joel Noble, the chair of the board, said it shouldn’t be considered a billboard because the structure would be drawing attention to something actually physically present at the property.

“The zoning code refers to billboard as outdoor off-site advertising,” he said. “So you’re advertising something that isn’t here, it’s over there. The sign that says, come see a play, go drink Coke — whatever it is, it’s not on site.”

Noble, a software engineer and past president of a Curtis Park neighborhood organization, essentially compared Carvana’s proposed project to a department store window display.

“This concept that they might pursue under this zone district would be a multi-story shopfront, in some sense,” he said. “Like when you’re passing by a shopfront and they’ve got glass windows, you can see what’s in there, and you can decide if it’s attractive to me, etc. In this case, it’s multiple stories of that in their concept.”

But wary of getting too far off topic, Noble reiterated that Carvana’s project was “not relevant” to whether or not it was appropriate to rezone the property.

Board member Don Elliot, a director with a land-use consulting firm, made a recommendation for how members could say focused.

“I’ve listened to this conversation, guys, but for me, it gets much, much easier if you forget Carvana,” he said. “You never saw Carvana, you never heard the word Carvana.”

Schultz, meanwhile, maintained that whether or not a property can have a billboard is contingent on that zoning, and thus it would be relevant if Carvana’s planned structure were to be considered a billboard.

Schultz said he has actually been to a Carvana tower. The closest to Denver are in Kansas City and Tempe, Arizona.

“This is a novelty,” he said. “They did this in other states to get around that. They have to make it functional … I’ve been on your board for six years. I have a right to ask the question about what this is going to be. Because to me, I’m going to argue it’s a billboard, and is that an allowable use.”

Subsequently, in what would be the final stab at defining Carvana’s planned project, Noble called it “a novel way to display your products in a very visible way.”

Then he called for a vote, which despite the earlier back-and-forth resulted in unanimity. Eight votes to recommend approval, and none against.

Carvana’s rezoning request now moves on to the Denver City Council, where it would ultimately need to be approved by a majority. It is set to be considered by the council’s Land Use, Transportation and Infrastructure Committee on Tuesday.

Leave a Reply