The founder of Denver gay nightclubs Tracks and the shuttered Fox Hole Lounge will be remembered in a memorial celebration on Aug. 4.

Martin “Marty” Chernoff, a straight Jewish man who expanded the Tracks brand to other cities in the 1980s and became a major landowner in both Union Station North and RiNo ahead of their redevelopment booms, died in May. He was 76.

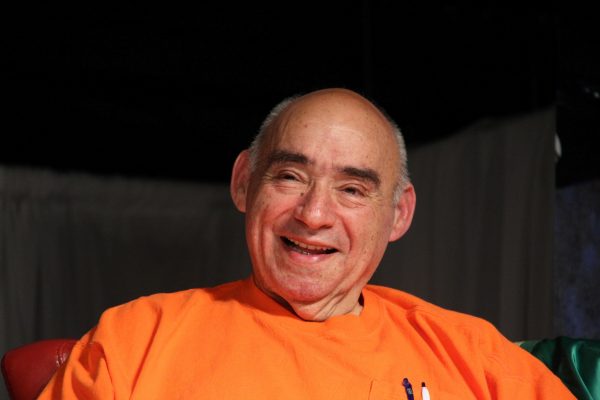

In a 2011 talk posted to YouTube, the source of all Chernoff’s quotes in this story, he described himself as “a people person,” but not necessarily the person one would expect to own popular nightclubs.

“I’ve certainly had my fair share of alcohol over the years, but … I’m really not a drinker,” Chernoff said. “And I’m not a dancer. I don’t particularly like loud music. I’m pretty tone deaf.”

“I’m really not a drinker,” the nightclub owner said in 2011. “And I’m not a dancer. I don’t particularly like loud music.” (Submitted)

Chernoff said he catered to the LGBTQ community decades before it was socially acceptable largely because he saw it as good business, but also because “my politics have always been financial conservatism and social liberalism.”

“I believe that anybody has a right to do anything they want with whatever they want however they want,” he said. “I just demand you give me those rights also.”

Chernoff was born in Brooklyn in 1942 and moved to Colorado to attend the University of Denver in 1959. He majored in math and statistics. After college, he worked in Los Angeles for five years as an engineer, a job he didn’t enjoy. He became a real estate broker, and worked in that field upon moving back to Colorado in the 1960s.

In the late 1960s, while scouting locations for a client who wanted to build a Formica kitchen cabinet factory, he stopped at a bar at 2936 Fox St., in what is now called Union Station North but was then referred to as The Bottoms. The owner, upon learning he worked in real estate, offered to sell him the business and the land.

Chernoff said he looked around and offered $32,000. The owner countered with $32,500 — the sum of his remaining mortgage and current bills — and when Chernoff accepted, handed him the keys and walked out.

“I think the next round’s on me,” Chernoff said he told the bar patrons. “I think I just bought this place.”

Chernoff’s LGBTQ nightclubs resulted in him being a significant landowner in Denver and Washington D.C. (Submitted)

Chernoff then proceeded to repeatedly sell the bar — the business, not the real estate — only to repossess it when the buyers defaulted. Several buyers in, Chernoff attended opening night, and was surprised to enter a “pitch black” establishment with “whips and chains hanging from the walls.”

“The one thing that stood out in my mind were not the backless chaps that people were wearing,” he said. “Was not the can of Vaseline on the bar. The thing that stood out in my mind — again, Jewish heritage — was the packed parking lot. I had never seen that many cars there before.”

When the owner defaulted, Chernoff took over the bar and rather than trying to resell the business, reopened it as “the same kind of club it had been when it closed.” It was called the Fox Hole Lounge.

Chernoff then partnered with a friend, Neil Feinstein, to buy a nearby property. In 1980, when the tenant moved out, the pair opened what became Tracks, another LGBTQ nightclub.

Later in the 1980s, Chernoff and Feinstein opened additional Tracks venues in Washington, D.C.; Tampa, Fla.; and New York, and considered locations in additional cities. But expansion was essentially halted and reversed by what Chernoff called “the dawn of the disaster called AIDS.”

By this point, however, Chernoff and Feinstein had became significant landowners in The Bottoms and southeastern D.C., according to Neil’s son Andrew Feinstein, who bought into the Exdo Properties business with Chernoff a decade ago after his father retired.

“In order to control their parking, they would buy all the lots around the club,” Feinstein said of Chernoff and his father.

The land in The Bottoms, until then a distressed neighborhood, attracted development interest when Coors Field was built nearby. Similarly, the D.C. property became more valuable when the Montreal Expos relocated to the city.

The Fox Hole Lounge continued to operate through the mid-2000s. Tracks’ Denver location closed by the late 1990s. But Chernoff’s former employees convinced him to later reopen it at its current location at 3500 Walnut St. in RiNo.

Once again, Chernoff purchased acres of property around the club, which became more valuable when RTD announced a commuter rail station would be built at 38th Avenue and Blake Street.

In the past decade, Chernoff and Andrew Feinstein have guided development in the area by selling portions of their holdings or partnering with other companies for projects such as The Hub, Industry and the World Trade Center.

“Marty approached real estate the way he approached people, which is no judgment,” Feinstein said.

One time Chernoff did misread things? Feinstein said the company and its event center by Tracks are called Exdo because Chernoff believed that the area, at the time referred to as Upper Larimer, would become known as ExDo, or Extended Downtown. Instead, it was branded RiNo, for River North.

Chernoff is survived by his wife Karen Jacobson, and their daughters Lisa Jacobson and Linda Moore. Doors open at Tracks for the memorial celebration at 1 p.m. on Aug. 4.

The founder of Denver gay nightclubs Tracks and the shuttered Fox Hole Lounge will be remembered in a memorial celebration on Aug. 4.

Martin “Marty” Chernoff, a straight Jewish man who expanded the Tracks brand to other cities in the 1980s and became a major landowner in both Union Station North and RiNo ahead of their redevelopment booms, died in May. He was 76.

In a 2011 talk posted to YouTube, the source of all Chernoff’s quotes in this story, he described himself as “a people person,” but not necessarily the person one would expect to own popular nightclubs.

“I’ve certainly had my fair share of alcohol over the years, but … I’m really not a drinker,” Chernoff said. “And I’m not a dancer. I don’t particularly like loud music. I’m pretty tone deaf.”

“I’m really not a drinker,” the nightclub owner said in 2011. “And I’m not a dancer. I don’t particularly like loud music.” (Submitted)

Chernoff said he catered to the LGBTQ community decades before it was socially acceptable largely because he saw it as good business, but also because “my politics have always been financial conservatism and social liberalism.”

“I believe that anybody has a right to do anything they want with whatever they want however they want,” he said. “I just demand you give me those rights also.”

Chernoff was born in Brooklyn in 1942 and moved to Colorado to attend the University of Denver in 1959. He majored in math and statistics. After college, he worked in Los Angeles for five years as an engineer, a job he didn’t enjoy. He became a real estate broker, and worked in that field upon moving back to Colorado in the 1960s.

In the late 1960s, while scouting locations for a client who wanted to build a Formica kitchen cabinet factory, he stopped at a bar at 2936 Fox St., in what is now called Union Station North but was then referred to as The Bottoms. The owner, upon learning he worked in real estate, offered to sell him the business and the land.

Chernoff said he looked around and offered $32,000. The owner countered with $32,500 — the sum of his remaining mortgage and current bills — and when Chernoff accepted, handed him the keys and walked out.

“I think the next round’s on me,” Chernoff said he told the bar patrons. “I think I just bought this place.”

Chernoff’s LGBTQ nightclubs resulted in him being a significant landowner in Denver and Washington D.C. (Submitted)

Chernoff then proceeded to repeatedly sell the bar — the business, not the real estate — only to repossess it when the buyers defaulted. Several buyers in, Chernoff attended opening night, and was surprised to enter a “pitch black” establishment with “whips and chains hanging from the walls.”

“The one thing that stood out in my mind were not the backless chaps that people were wearing,” he said. “Was not the can of Vaseline on the bar. The thing that stood out in my mind — again, Jewish heritage — was the packed parking lot. I had never seen that many cars there before.”

When the owner defaulted, Chernoff took over the bar and rather than trying to resell the business, reopened it as “the same kind of club it had been when it closed.” It was called the Fox Hole Lounge.

Chernoff then partnered with a friend, Neil Feinstein, to buy a nearby property. In 1980, when the tenant moved out, the pair opened what became Tracks, another LGBTQ nightclub.

Later in the 1980s, Chernoff and Feinstein opened additional Tracks venues in Washington, D.C.; Tampa, Fla.; and New York, and considered locations in additional cities. But expansion was essentially halted and reversed by what Chernoff called “the dawn of the disaster called AIDS.”

By this point, however, Chernoff and Feinstein had became significant landowners in The Bottoms and southeastern D.C., according to Neil’s son Andrew Feinstein, who bought into the Exdo Properties business with Chernoff a decade ago after his father retired.

“In order to control their parking, they would buy all the lots around the club,” Feinstein said of Chernoff and his father.

The land in The Bottoms, until then a distressed neighborhood, attracted development interest when Coors Field was built nearby. Similarly, the D.C. property became more valuable when the Montreal Expos relocated to the city.

The Fox Hole Lounge continued to operate through the mid-2000s. Tracks’ Denver location closed by the late 1990s. But Chernoff’s former employees convinced him to later reopen it at its current location at 3500 Walnut St. in RiNo.

Once again, Chernoff purchased acres of property around the club, which became more valuable when RTD announced a commuter rail station would be built at 38th Avenue and Blake Street.

In the past decade, Chernoff and Andrew Feinstein have guided development in the area by selling portions of their holdings or partnering with other companies for projects such as The Hub, Industry and the World Trade Center.

“Marty approached real estate the way he approached people, which is no judgment,” Feinstein said.

One time Chernoff did misread things? Feinstein said the company and its event center by Tracks are called Exdo because Chernoff believed that the area, at the time referred to as Upper Larimer, would become known as ExDo, or Extended Downtown. Instead, it was branded RiNo, for River North.

Chernoff is survived by his wife Karen Jacobson, and their daughters Lisa Jacobson and Linda Moore. Doors open at Tracks for the memorial celebration at 1 p.m. on Aug. 4.

Leave a Reply