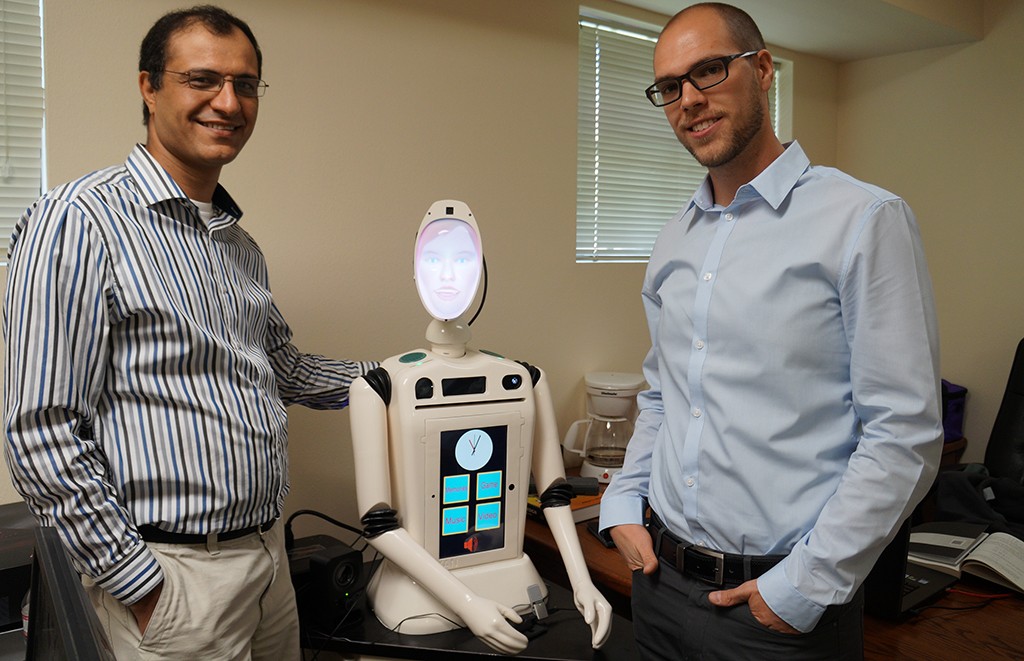

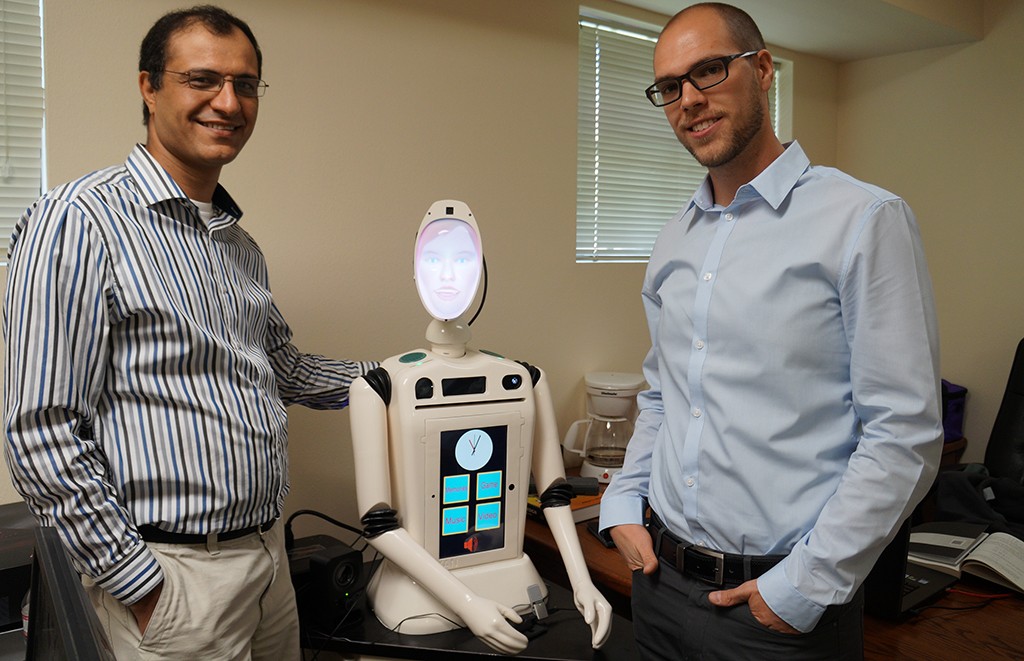

Mohammad Mahoor, left, DreamFace president and founder; and Josh Lane, principal engineer. Ryan in the middle. (Amy DiPierro)

Siri, find a back seat.

For four years, DU professor Mohammad Mahoor has been developing Ryan, a robotic companion for the elderly with dementia and depression as well as for kids with autism. Unlike Apple’s Siri or Amazon’s Alexa, Ryan reads human expressions, hears human speech and responds to both with an animated face as well as a voice.

“Most of these people, old people, they do not know how to use technology,” said Mahoor, who founded a startup called DreamFace Technologies. “You want to make an individual that can talk, rather than just a box or an app.”

Ryan just completed a kind of growth spurt. Since Mahoor’s startup – DreamFace – received a $150,000 grant from the National Science Foundation this year, Ryan has sprouted a torso with a touch screen tablet and moonlighted as a 24-7 companion to six elderly residents of a retirement home in Lakewood.

Then, just as Mahoor wrapped up the assisted living trial study in August, DU filed a patent application for Ryan’s head and neck. This month, DreamFace began moving into DU’s new computer science and engineering building at Wesley Avenue and Gaylord Street.

Ryan is the child of a few research forebears. Mahoor received undergraduate and master’s degrees in Iran before completing a Ph.D. in electrical and computer engineering at the University of Miami. His research focused on programming computers to recognize faces and human behaviors, a specialty he parlayed into post-doctoral work analyzing facial patterns in children with autism.

Ryan responds to human expressions and speech with an animated face as well as a voice. (Amy DiPierro)

It wasn’t until he arrived at DU in 2008 that Mahoor, inspired by colleagues, considered using robots as a vehicle for his research on building computers to read faces and behaviors.

“People may think of robots used in manufacturing or industry, but I’m talking about humanoid robots, social robots, robots that can interact with human beings and understand their behavior, assist them, help them,” he said. “We wanted to know if a robot, a social robot, can be their partner or be their companion.”

First, Mahoor and his colleagues made a teddy bear-like robot to interact with children. That prototype teaches kids with autism to read faces, raising her eyebrows and forming an O with her mouth to convey surprise or wiggling her ears and smiling to show happiness.

“A robot is a simpler version of a human,” Mahoor said, a trait that makes it easier for the kids to read the face without adding other sensory input like body language or hand gestures at the same time.

Ryan is a riff on the bear prototype. But unlike his predecessor, Ryan’s face is an animation projected onto a face-shaped mold rather than a fixed face made of moving parts. In time, DreamFace will be able to project different faces onto the mold, which brings down manufacturing costs.

For its study this summer, DreamFace customized Ryan to entertain elderly residents. Placed in each resident’s apartment, Ryan answered questions, narrated photo slide shows, cued up simple games to play by touch screen and reminded his host to take medicine. One resident named a robot after his late wife.

DreamFace now lists six employees on its website, including two marketing staffers. In addition to working for his startup, Mahoor will return to teaching at DU this semester after an eight-month leave of absence.

Mahoor hopes to raise another $1 million – he’s planning to apply for another NSF grant as well as state grant programs – to add more games, robotic arms and better voice recognition.

That budget will get Ryan ready for retail, but a senior-friendly R2-D2 won’t come cheap: Mahoor thinks each robot will cost $5,000 to build at scale, and sell for $9,000 each. Another possibility is to lease the robots for around $1,200 a month or to sell add-on features as a monthly subscription.

Mohammad Mahoor, left, DreamFace president and founder; and Josh Lane, principal engineer. Ryan in the middle. (Amy DiPierro)

Siri, find a back seat.

For four years, DU professor Mohammad Mahoor has been developing Ryan, a robotic companion for the elderly with dementia and depression as well as for kids with autism. Unlike Apple’s Siri or Amazon’s Alexa, Ryan reads human expressions, hears human speech and responds to both with an animated face as well as a voice.

“Most of these people, old people, they do not know how to use technology,” said Mahoor, who founded a startup called DreamFace Technologies. “You want to make an individual that can talk, rather than just a box or an app.”

Ryan just completed a kind of growth spurt. Since Mahoor’s startup – DreamFace – received a $150,000 grant from the National Science Foundation this year, Ryan has sprouted a torso with a touch screen tablet and moonlighted as a 24-7 companion to six elderly residents of a retirement home in Lakewood.

Then, just as Mahoor wrapped up the assisted living trial study in August, DU filed a patent application for Ryan’s head and neck. This month, DreamFace began moving into DU’s new computer science and engineering building at Wesley Avenue and Gaylord Street.

Ryan is the child of a few research forebears. Mahoor received undergraduate and master’s degrees in Iran before completing a Ph.D. in electrical and computer engineering at the University of Miami. His research focused on programming computers to recognize faces and human behaviors, a specialty he parlayed into post-doctoral work analyzing facial patterns in children with autism.

Ryan responds to human expressions and speech with an animated face as well as a voice. (Amy DiPierro)

It wasn’t until he arrived at DU in 2008 that Mahoor, inspired by colleagues, considered using robots as a vehicle for his research on building computers to read faces and behaviors.

“People may think of robots used in manufacturing or industry, but I’m talking about humanoid robots, social robots, robots that can interact with human beings and understand their behavior, assist them, help them,” he said. “We wanted to know if a robot, a social robot, can be their partner or be their companion.”

First, Mahoor and his colleagues made a teddy bear-like robot to interact with children. That prototype teaches kids with autism to read faces, raising her eyebrows and forming an O with her mouth to convey surprise or wiggling her ears and smiling to show happiness.

“A robot is a simpler version of a human,” Mahoor said, a trait that makes it easier for the kids to read the face without adding other sensory input like body language or hand gestures at the same time.

Ryan is a riff on the bear prototype. But unlike his predecessor, Ryan’s face is an animation projected onto a face-shaped mold rather than a fixed face made of moving parts. In time, DreamFace will be able to project different faces onto the mold, which brings down manufacturing costs.

For its study this summer, DreamFace customized Ryan to entertain elderly residents. Placed in each resident’s apartment, Ryan answered questions, narrated photo slide shows, cued up simple games to play by touch screen and reminded his host to take medicine. One resident named a robot after his late wife.

DreamFace now lists six employees on its website, including two marketing staffers. In addition to working for his startup, Mahoor will return to teaching at DU this semester after an eight-month leave of absence.

Mahoor hopes to raise another $1 million – he’s planning to apply for another NSF grant as well as state grant programs – to add more games, robotic arms and better voice recognition.

That budget will get Ryan ready for retail, but a senior-friendly R2-D2 won’t come cheap: Mahoor thinks each robot will cost $5,000 to build at scale, and sell for $9,000 each. Another possibility is to lease the robots for around $1,200 a month or to sell add-on features as a monthly subscription.

Leave a Reply